Last month, a letter by Iranian artist Mania Akbari circulated on social media. It was addressed to MK2, the distribution rights holder for the film 10. Akbari claimed that the footage used in the film belonged to herself, and accused Abbas Kiarostami not only with stealing her work but also with sexual assault. As these claims stirred up controversies across social media, we contacted Akbari to listen her story in all its details.

Interview: Fatma Edemen

Trigger Warning: This article includes descriptions and discussions of sexual violence and abuse that may be triggering to some readers.

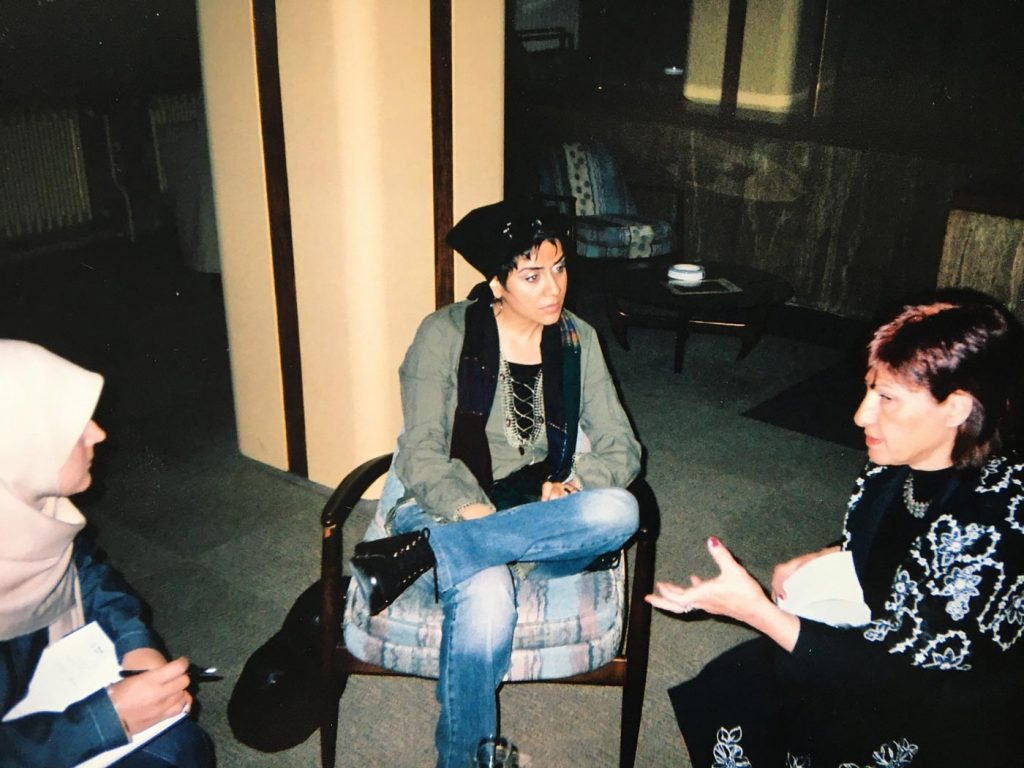

I met Mania Akbari during the Flying Broom International Women’s Film Festival. She visited the festival multiple times, and in 2019 she won the FIPRESCI Award for her film A Moon for My Father. Even though we never saw each other in person, we knew each other through the chat group of the festival. It was thanks to Mania that I got to know the Iranian #MeToo movement and one of its outspoken leaders, Shaghayegh Norouzi. As keen advocates of women’s emancipation, Mania and Shaghayegh also took initiatives to help refugee women in need of legal support in Turkey.1 Working for this campaign brought us yet closer.

On May 14, Mania shared a very important message with us in the group chat. The message contained a letter. Touched by its content, I asked Mania if she would talk more about it in an interview. She kindly accepted my invitation and we met the following week. It was a long, traumatic and emotionally challenging talk. In what follows we will share Mania’s story with you.

“It has taken me all these years to even acknowledge and recognize what happened to me, to call it what it was, let alone talk about it publicly.”

Mania’s letter was addressed to the distribution company MK2, which holds the distribution rights of the film 10 (Dah, 2002). In this letter Mania claims that she herself filmed 10 and her work was stolen by Abbas Kiarostami, and that he abused her both mentally and physically. For over a year there was no response from MK2.

When Mania discovered that the film was scheduled to be shown as part of a Kiarostami retrospective at the BFI in London, where she now lives, she took the decision to share this letter more widely by sending it to her email list. The reactions were mixed; while there was a lot of support, others questioned why she had waited for twenty years to speak out about the abuse, plagiarism, and sexual harassment.

One of the things that the #MeToo movement has made visible is that the mental and physical abuse of women by established, powerful men has been appallingly systemic in the film and entertainment industry, as in many workplaces. #MeToo was a movement which gave women the courage to speak out and disclose the abuse collectively. In a post-#MeToo context, we now know that it takes time, courage, and solidarity to process such traumatic experiences. For Mania, too, it was difficult to process everything she experienced and to have the strength to disclose it publicly.

“It wasn’t easy even to start thinking about it. My psychotherapist in London, my partner Douglas White, and many feminist friends helped me step by step to process this. I’m not scared of this memory anymore; I’m also not scared of his name. Of course, he is a big name around the world. He reminded me of this many times. ‘Nobody will believe you’, he said, and I kept quiet. As a young filmmaker, I respected him and I looked up to him.”

THE MAKING OF 10

Mania claims that the footage from 10 was a personal project. When Mania shot the rushes, she wasn’t planning to produce a film from them. These rushes, which were edited to become 10, were personal recordings of her and her surroundings. She had hours of footage, which Kiarostami discovered and said he wanted to develop into a script. However, Kiarostami ended up never writing a script; he just edited the existing footage. She says, “At the end of 10, you see that he didn’t add credits for its director, writer, or actors. He just wrote our names, Abbas Kiarostami and Mania Akbari.”2

The premiere of 10 at the Cannes Film Festival was a traumatic turning point for Mania. Until their trip to Cannes, Kiarostami told her that this was “your film, I just edited your rushes.” Mania was surprised to hear that 10 made it to the official selection at Cannes. Before they departed, Kiarostami showed her the final cut. They watched it at her home together. This version didn’t have any end titles. However, shortly before the screening in Cannes, things changed.

“He told me, ‘You know Mania, this film is fiction.’ I was shocked, because I never had this feeling about the film. He told me ‘Just follow me, repeat everything I say.’ He told me that the film would never have been selected for Cannes and win a prize if we didn’t say it was a fiction that he had directed it. He convinced me to say that we were actors in the film, and this is how he sold the film to the world. This was his way to gain prestige and commercial success.”

In the press conference, when Mania received the first question, which was about acting, she was shocked and couldn’t answer. She relates how, as she was trying to reply with an abstract answer Kiarostami took the microphone to assert that the film was fiction, and that he started to explain how he had given directions to the actors.

“I was 26, on a stage in front of hundreds of people, sitting next to an acclaimed director. I felt I had no choice but to confirm what he said. He wanted to tell the world that he directed this film. He wanted to tell how the boy acted, so this became the truth.”

Mania believes that, by positioning her as an actress, Kiarostami wanted everyone to think that her career started with him. However, before she met Kiarostami, Mania was an aspiring filmmaker in her own right, who had worked with the Iranian woman filmmaker Mahvash Sheikholeslami. Looking back, Mania acknowledges the importance of working with Sheikholeslami in the early stages of her career.

“I was a young woman trying to find myself in a traditional society, and my therapist suggested that I do something creative. Back then, shortly after I had met Mahvash, my partner had bought me a small camera. I picked it up and started to film in my home, in the kitchen, in my car. This is the camera I attached to the dashboard to record the footage in 10. I lived with my husband and three kids. Two were from his former marriage, one was from mine. It wasn’t easy and the camera helped me to look at life through a different perspective, to look at myself, to understand who I was as an artist, a woman, a mother and a wife in Iranian Islamic society. It helped me find my identity. This was the beginning of my life’s work as a filmmaker. As a young woman aspiring to become a filmmaker, my encounter with Mahvash Sheikholeslami was a life-changing experience. I became her assistant and later her cinematographer. But in Kiarostami’s version of my personal story, I was a painter who then acted in his film.

I’m trying to rewrite that fabricated past. I’m trying to credit all those names that played a role in building up my career. But it’s not easy, I couldn’t even add these in Wikipedia. Male power can write the story; just as Kiarostami wrote my story. He wanted to convince me that it was better to be known with his name, because no one knew Mahvash.”

Mania attended three of 10’s screenings- the premiere at Cannes, ICA in London, and then Thessaloniki International Film Festival. It was after Thessaloniki that Mania says that she decided to stay away from Kiarostami and his circle. “I left the festival and returned to Iran. I sent a long fax to Kiarostami explaining how he had damaged my belief in art and cinema, and I no longer wanted to tell these lies. Then I went to talk to his son (Bahman Kiarostami). I told him, ‘Your father is a liar.’”

After this, Kiarostami asked to meet Mania’s sister Roya Akbari, who also appeared in 10, in his own house. Roya recounts how he shouted, swore and intimidated her, telling her that no one would believe Mania, and that without him this film would be in the bin. Mania alleges that at this point he started to circulate rumours about her, telling people that she was mentally unstable and not to be trusted.

“I still love his films, I love Close Up (Nema-ye Nazdik, 1990), but it’s also true that he used his power and prestige against a woman, against a woman’s story. He destroyed me in the Iranian society. He claimed that I had mental problems and that I was dangerous. I was half way through a documentary about single mothers in Tehran, then suddenly all the women dropped out of the project. Nobody contacted me; it was a scary and lonely time. And so I decided to remain completely quiet.”

Mania was scared that Kiarostami was attempting to damage her later films and her future career. She kept the production of her first feature-length film, which she made shortly before being diagnosed with cancer, 20 Fingers (20 Angosht, 2004), within a small group and didn’t reveal it to Kiarostami. When it was selected for the 61st Venice Film Festival3, she was more scared than happy, fearing that Kiarostami would be infuriated. She did her best to placate and appease Kiarostami, telling him things he wanted to hear.

“When 20 Fingers came out, he was upset. I had dedicated the film to him. I told him, ‘I dedicated my first feature film to you, please don’t destroy me.’”

She said to Kiarostami, “Everything that I have is thanks to you, and let’s forget about Ten.” Mania wanted to show him that she wasn’t a threat to him and that she wasn’t planning to expose him.

“‘Nobody will believe you’, he said, and I kept quiet. As a young filmmaker, I respected him and I looked up to him. I’m not scared of this memory anymore; I’m also not scared of his name.”

Mania goes on to outline the lies that she says Kiarostami told around 10’s production. For instance, Mania had to wear a hijab during the filming, as is mandatory for women in Iran when driving on the street. She occasionally had to adjust the top of her hijab to keep it in place. However, she says, Kiarostami manipulated this situation to reinforce his claim about having shot the film himself.4

“He told the world, I was putting my hand to my scarf because there was a headphone in my ear, and he was directing me. Can you believe it? Twenty years ago, shooting with a headphone in my ear. He was only able to say this because of the hijab. Can you see the metaphor of control here? He is in my ear. Women have been fighting against mandatory hijab for forty years, and here he is using it to take control of me.”

“When I was in Paris for a screening of 20 Fingers, a journalist asked me about the sex worker in 10. I told her that it was my sister acting. The journalist replied, ‘Is Kiarostami a liar? Or are you a liar? Because when I interviewed him (Kiarostami), he told me that he wrote the dialogue and that the girl who played the sex worker had escaped from Iran to Canada, and he did not show her face on purpose.’ I was shocked and said, ‘Sorry, maybe he is right.’ I couldn’t explain because I feared him (Kiarostami). I told everything that he wanted. Do you know how painful that was? When I returned to Iran, I called him. I said, ‘Please let me know exactly what stories you are telling people about this film, because if I don’t know what you are saying then I may say different things. He replied, ‘You promised me that you would only talk about your film 20 Fingers, andnot about 10 anymore.’ I asked what I could do if people asked me about 10. He replied that I should read all his interviews and say the same things, then added ‘Just don’t talk about my films, talk about your film.’ At the end of the conversation he said, ‘I hope you know that if people are screening your film 20 Fingers it is because of my name, not yours. If I made a film of an empty black screen the world would talk about it. You have to know that without 10 you would still be in your studio making paintings of Katayoun (Taleidzadeh).’”

It was Katayoun who was responsible for one of the most iconic scenes in 10, in which the young woman removes her hijab to reveal her bald head. Mania is particularly angered by the lies around this scene:

“Every amazing thing Katayoun did in the film came directly from her. There was no male figure hidden behind the story forming or directing these inner experiences of a woman. When Katayoun removed her white head scarf to show her shaved head, she had never met Abbas Kiarostami. This was an expression of a deep female pain, and its sole author was Katayoun, drawing on her experience and her courage; and the sole recorder was me, as Katayoun’s companion and sympathizer. This was a moment of female strength and solidarity. Why should this man be free to steal this and claim it as part of his own genius?”

Concerning the sex worker scene in the movie, Kiarostami repeatedly claimed that he met with numerous sex workers in order to write the script for this scene, and that he auditioned many women to play this role. According to Mania and her sister Roya, the sex worker was improvised by Roya. Roya also plays another part in the film. She says she had never met Kiarostami at the time of filming. Mania recalls that they could only record audio because they forgot to open the camera lens cover while recording. Kiarostami would claim that he didn’t show the actress’ face to avoid the audience judging this character.

Mania says that Kiarostami went to extreme lengths to fabricate the story about 10’s creation. This included filming fake backstage footage. One of these films was released by Kiarostami’s family earlier this year as a rebuttal to Mania’s claims, but in her opinion it only serves to support her story.

“He told us he needed to reshoot the scene with Katayoun, that we should wear the same clothes, and set everything up the same. He invited his son Bahman to film it. This was before the final edit of the film so I thought perhaps he wanted to use this footage. But none of it appeared in the film. In the backstage footage you can see that our clothes are a little different and you can even hear me complaining that Katayoun cannot replicate the same performance. I realise now he was trying to create fake evidence.”

This brings Mania back to the subject of 10’s end credits:

“The reality is that all nearly these people were my immediate family. Roya and Mandana were my sisters. He used their married names even though they wouldn’t have used these names themselves. Obviously he didn’t want the credits to read: Mania Akbari, Roya Akbari, Mandana Akbari. But the truth is there were only two people in this film who were not my immediate family. One was my friend and model Katayoun. The other was the ‘religious woman’, who was just a member of the public I picked up by chance while driving. This is a very normal thing to do in Tehran. We also never see her face, because there was no camera on her. But, again, Kiarostami said that he hid it. In the film we see her getting out of the car, but this isn’t her at all, this is me! One day Kiarostami told me to wear a black Chador with lots of clothes underneath so that I looked fat, and that he wanted to film me getting out of the car. He didn’t say why. The first time he showed me 10 I saw how he cut from my face to the religious woman getting out of the car, which was me in the chador, but we only see my back. I was shocked. He told me, ‘This is the magic of cinema. Cinema is a lie! You have to be a good liar. You have to believe your lie and then people will believe you.’”

According to Mania, on another occasion, after the film’s release, he invited Roya to shoot a scene, which she imagined was for a new production. When she arrived she realised that the script consisted of exactly same words that she said in 10. So she refused to participate, at which point, she says, Kiarostami stormed out.

CONFRONTING THE TRAUMA

Mania relates how, in time, both she and Kiarostami started to act as if nothing had happened between them. They emailed from time to time. When he died, Mania’s partner Douglas was with her, trying to support her through her tears. Later, he realized something was changing. Only after Kiarostami died, Mania could speak with her feminist friends, partner, and therapist. She was able to disclose that Kiarostami raped her, and she had forced herself not to acknowledge it all these years. The traumas she had hidden from her mind were now beginning to surface.

“It was my therapist who first spotted this. My therapist realized I avoided talking about him (Kiarostami); I was telling positive things all the time to ward off the topic. Step by step, my therapist guided me.”

Mania could only begin to acknowledge the truth of what happened in the past couple of years. Up until recently she was in denial, not wanting to see herself as weak.

“I always thought I was a strong woman, and nobody could hurt me. I was married. I had a good relationship with my husband. He was so proud that Kiarostami was coming to our house to watch films with his wife. I was very young then, about 24-25 years old.

One day he (Kiarostami) called me and asked me when Morteza (Mania’s ex-husband) would come home. I said at eight. ‘I’m coming at seven o’clock, because I have to go a bit early tonight,’ he said. He visited our flat quite often. We had a lovely, artistic home that he liked. My partner used to cook dinner, while we watched films together. I used to call him Mr. Kiarostami; I never used his first name. He was a hero to me, a teacher, a master.

On that day, he came to my flat with a plastic bag. Inside were four beers and a package of pistachio. It was Thursday night, our kids were at their mother and fathers’ homes. At that time, I used to smoke occasionally, I quit completely after cancer. I walked towards the window to smoke. He came behind me and grabbed me from behind. He pulled down my underwear. I froze. He didn’t talk to me or try to kiss me. He was strong. He raped me. I couldn’t believe it; I thought that I had died. No kiss, no touch, no affection – it was violence. Then he heard the door. We had a bell that hung from the ceiling in front of our door so we knew if our kids were coming in or out. My husband was entering the flat and the bell rang, that is why Kiarostami stopped and put his shirt over his trousers. I heard his zip.

I was living in Iran; I was married. I couldn’t say anything to my husband. I thought to myself ‘He was drunk; he wasn’t himself, maybe I laughed too hard, or wore too much makeup.’ I forced myself to believe it. I thought it was my fault. I told myself ‘Forget it, forgive him. I have a husband, I have kids. He is Kiarostami, I am sure he was just drunk!’”

After this, Kiarostami acted as if nothing had happened. Not knowing what to do, Mania followed his lead. She tried to forgive him and decided to forget about it.

“When we went to London for the screening at the ICA, I was in the process of a divorce. We were staying in the same hotel on the same floor. He (Kiarostami) had been drinking, and we were walking to our rooms. It was around 2 am. Our rooms were opposite each other. I put the key in my door and that’s when I felt him grab my breasts from behind. He raped me there in the corridor, exactly as he had done in my flat. I never saw his face while it was happening and he never said anything. When it was over he went straight into his room. I went into my room and cried on the bed. I remember thinking how strange it was that he hadn’t invited me to his room, or come into mine. I was so confused. It was clear he wasn’t looking for love. Before this happened, he had given me a ring as a gift; not as a marriage ring, just a ring for my birthday. He told me ‘I bought this ring in Paris for my amazing actress in 10.’ When we were alone he would call me the best actress in the world, but in front of journalist he called me Na Bazigar, or non-actress, which was a word that he invented. I decided to speak with him the next day at breakfast. He told me he wanted to be left alone; he couldn’t sleep last night. He said, ‘I don’t want to talk to you, have your coffee by yourself.’ Then I thought, okay, he was ashamed because he was drinking. I convinced myself he was drunk last night and didn’t want to talk because he was embarrassed.

Even now I ask myself what I should have done differently. How could I have stopped this? Should I have told someone, and if so, then who? My husband? Someone at the hotel? Someone from MK2? None of these things even remotely crossed my mind. It was just a thing that happened and I did my best to forget it and move on. I was alone with him in London, a very foreign place, I hardly spoke any English. But the real truth is that I didn’t really know what had happened to me. It was only years later, when I told my therapist this story that she explained it was rape.

It has taken me all these years to even acknowledge and recognize what happened to me, to call it what it was, let alone talk about it publicly.”

Mania didn’t want to believe what she was going through and wanted to think that Kiarostami respected her. Yet, now looking back, she says she can see clearly that Kiarostami not only plagiarised her work, but he also sexually assaulted her. Mania believes that his main motivation was to have complete control over her.

During this short trip to London Mania also conducted an interview at the ICA with the respected film critic, and close friend of Kiarostami, Geoff Andrew. She recounts how Kiarostami instructed her to repeat everything he had told her, and how he sat next to her throughout the interview. This interview would become the basis of the seminal monograph about the film, published in 2005 by the BFI, re-iterating and cementing Kiarostami’s version in great detail.

In 2004 Kiarostami released the film Ten on 10, a documentary which tells his story about the film’s creation. Mania points out that it is notable that none of the participants of the film agreed to take part in this documentary, and that it was the only time Kiarostami sought to outline his filmmaking practice in such detail.

During our conversation, Mania repeatedly underlined how famous and powerful Kiarostami was, both in Iran and internationally. This made it so hard to stand up against him. Now, above all, Mania wants to fight for herself and other women facing all sorts of similar abuses – a fight she didn’t dare take on in the past.

Shortly after 20 Fingers, Mania was diagnosed with Stage 4 breast cancer. The cancer was advanced, and doctors feared that she had little chance of survival. She was only 28. She describes how Kiarostami quickly came to the hospital upon hearing the news. Mania believes that he was probably afraid that she might disclose what happened, or that perhaps he felt guilty. At the hospital, Mania told Kiarostami that she wanted to make a film about her own story and cancer. Later, she started to film 10+4; somehow, she wanted to reclaim her narrative.

Mania travelled to Italy at regular intervals to receive chemotherapy and spent the rest of her time back in her studio in Iran.

“He (Kiarostami) started to visit my studio regularly. One day, he wanted to watch my rushes. He said, ‘It’s beautiful, amazing, poetic.’ He offered to work with me on this film. I started to shake. I thought, oh my God, it is happening again like with 10.

The next day I sent him a fax message. I told him that, if I die, he could edit my rushes, but if I survive, I wanted to do it. He stopped coming to my studio. Before this, every single day, he visited me and brought kebab and rice. He disappeared after the fax. I called him, but he hung up on me. He no longer cared if I was dying.”

Mania adds how gaslighting was another tool Kiarostami used to control her, alleging that he defamed her for years, spreading the word that she was mentally ill. This way, he’d ensure that no one would believe her should she speak out – be it about the film, or about the sexual abuse. She describes how Kiarostami used both her divorce and her cancer to reinforce this false image. According to Mania, Kiarostami was loved, especially in France, and he had connections and power there. She claims that he particularly talked badly about her there. “After I told him about 10+4, and he stopped contacting me, I discovered that he was telling people that I had been in a psychiatric hospital, when in fact I was having cancer treatment. For years people would ask me about this. It is unbelievable that I need to state this, but I have never been to a mental hospital,” she says.

After she started to speak up, Mania faced resistance from Kiarostami’s sons, who tried to invalidate her story. They have been vociferous in their defence of the director, particularly his son Ahmad, in ways which Mania believes continue the cycle of abuse. It is for this reason that she insists on being so thorough about all the details surrounding the filming of 10.

“They will do everything they can to discredit me. They published private emails I had sent to their father, calling me out because they showed respect to him. Yes I had respect for him. Yes I cried when he died. This man was a huge part of my life. Anyone that has experienced a relationship such as this may understand how confusing it can be. When he died I had never acknowledged the things he had done to me.

I didn’t hate him. For years I made excuses for him, and I still find myself doing this. But I am also ready to accept what he did to me. Shortly before his death, when he was very sick, I called him. He told me, ‘I loved you, but you were stupid, and you never understood. You told my son I am a liar.’ I cried so hard after that call. Years later I’m still trying to process those words.

In the last two years, I was invited to participate in retrospective screenings of Kiarostami’s work. I never accepted any of these invitations. I respectfully declined. If I wanted fame, attention, money, it would be much easier for me to attend these events. Before the letters, a journalist from MK2 called me for a contribution to the retrospective book about Kiarostami. I replied that I would accept, but I would only tell the truth. I never heard back from the writer.

I am here to fight these power structures. I want them to stop distributing and screening 10. They said I wanted money. I don’t want money; I have never mentioned money. It is worth mentioning that none of the women involved in the film ever received a single cent for their participation in 10, which would surely be unusual if they were acting in a film written and directed by Kiarostami. But I’ll say it again, to be clear. None of us want any money. I don’t want to sue anyone. If MK2 feel they have profited unfairly from these women, whether knowingly or not, then we can happily discuss which charity they should donate these profits to. I don’t want money, I don’t want credit, I don’t want attention. I want history to record what really happened. Why should this man be free to steal the work and experiences of all these women and claim it for himself? I also want to speak for other women. I am sure it is not just me. I want to stop public screenings of 10. It is a lie, it is a theft, and it is very hard for me to see this work declared as part of my rapist’s canon.”

I am here to fight these power structures. I want them to stop distributing and screening 10. I want history to record what really happened. Why should this man be free to steal the work and experiences of all these women and claim it for himself?

Mania seems concerned to cover every moment of her experiences with Kiarostami, especially concerning 10, in exhaustive detail, fearing that the smallest omission will be jumped on by the Kiarostami family to discredit her. ‘And he was clever,’ she says, ‘he knew how to cover his tracks.’ On the day they were ‘reshooting’ Katayoun, she describes how Kiarostami asked her husband, Morteza Tabababai, to photograph her and Kiarostami next to the large video camera MK2 had provided him with. She reflects, “I didn’t understand at the time. He sent these photos to MK2, and these now serve as part of the evidence that he shot the film, but it’s so obvious this camera would have never fitted on the dashboard of my car. I used the small camera my husband had bought me long before.”

A couple of days before our conversation, Mania told me that the British Film Institute (BFI) decided to remove 10 from the Abbas Kiarostami Retrospective. I asked her if she feels stronger after this decision. She says she feels stronger with the emerging Iranian #MeToo movement and her feminist activist friends in London.

It was difficult for me to listen to Mania and understand her fight against injustices she experienced and carried for years. I believe sharing her story is a healing process for her. However, she is not only trying to heal herself; she is also trying to help and organise others to fight against male dominance both in the film industry and in every aspect of life.