Text by Volga Deniz Çakmak

Translated to English from Turkish by Duygu Çınga

The shorts referred to in this text can be viewed on Altyazi’s YouTube channel.

The pandemic is reshaping our social reality. In our private spheres, we are grappling with the consequences of this imposed change. Our participation in social life – through whatever way we used to prefer – has been restricted. The need to reconnect with the crowds – to be a part of the big whole again – has brought unique experiences. In the face of a new norm emerging at a global scale under “state of emergency”, creativity and creative expressions, already hit hard by the current political climate, have also got their share.

Cinema industry in Turkey has been under extreme pressure since 2014. In that year, there were censorship cases at Antalya Golden Orange International Film Festival’s documentary section and consequently lawsuits were brought against censored documentaries for “constituting crime.” Special regulations were imposed by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, such as classification/evaluation and the requirement for a registration certificate, to facilitate surveillance. Documentary filmmaking has been thus restricted as films without a registration certificate have been banned from commercial distribution. The process of classification/evaluation has become an apparatus of censorship in the hands of the ministry. The monopolisation of cinema chains resulted in the closure of independent and historical cinemas, which has made it impossible for independent films to find a screening venue. All of these brought a need to establish new spaces to ponder on potential solutions to overcome the current crisis (namely, “the crisis of freedom of expression” considering its social outcomes). The healing power of collective thinking and production has become more important than ever in this setting.

The screenings by Altyazı Fasikül: Free Cinema are among the activities opening up new spaces of expression in this period of crisis. They attempt to fulfil such a need by bringing together documentary makers, video-activists and independent filmmakers. When the lockdown came, Altyazı Fasikül issued a call for short documentaries addressing the topic of looking outside. Eleven short films that responded to the call were streamed online. So offered Altyazı Fasikül an alternative channel both to sustain filmmaking under taxing conditions of the lockdown and to comprehend the spirit of the times.

RETHINKING THE INSIDE VERSUS THE OUTSIDE

The dichotomy of “inside-outside”, which lies at the core of the shorts in the series, solicited a reflection on how we experienced the the spatial restrictions imposed. Yet, in the series the meaning is not limited to a straightforward binary opposition defined by physical spatial boundaries. In these shorts, conveying transformations in the public and private spaces through creative stories, images, and sound design, what happens “inside” is not just about domestic isolation, nor is the “outside” equated with the life in the public space. Each of the films in this selection is a product of craftsmanship that creates meaning through viewing human activities as a whole, and forms a unique language with various stylistic experiments. Yet, they do have a common point as well: Each film is based on the idea that the flow from the inside to the outside is never unidirectional; it is always disrupted by a moment of intellectual tremor. The images conveying these moments of disruption are quite versatile in each film.

What happens “inside” is not just about domestic isolation, nor is the “outside” equated with the transformation of life in the public space.

In the face of this extraordinary moment in history, each filmmaker makes use of their own coping mechanisms to reflect on the flow that connects inside and outside, and the disruptions thereof. The images largely reflect the state of being confined, which is at the kernel of the narratives, putting forward different questions each time. The layers of the shell extending from inside to outside are formed by conceptual sets such as the public vs. the private, the unconscious vs. the conscious, individual memory vs. collective memory, isolation vs. solidarity, sounds of the private space vs. sounds of the public space, past vs. present, and myth vs. reality. The desire of each piece to reach a whole brings together all these pursuits at a crossroads.

LAYERS OF THE MEMORY: SPACE AND WITNESSING

This section of the article will focus on the films dealing with the characteristics of memories, exploring remembrance and oblivion, the two elements of individual and collective memory, in relation to each other, yet through different means. The first one is The Balcony and Our Dreams by Aylin Kuryel. At the live conversation held with her following the first screening of the film on Youtube1, Kuryel stated that upon realizing that she had more dreams than before during the lockdown and remembered her dreams more than ever, she decided to make a short movie reflecting upon this situation. She thus began to collect records of dreams from people around her. The film seeks the link between the private space, namely what is “inside”, and the public space, in other words, the “outside,” presenting the balcony as the place that opens up from inside to outside. Throughout the film, we watch the life outside through a camera angle viewing the street from a balcony, yet the director does not equate this gaze with a voyeuristic eye watching the street from a balcony. We witness the flow of anxiety, fear or joviality in households towards the public space through the image of a balcony and dream narratives. We see images of the same street during the lockdown through fragments of day and night, around the statue of a sleeping woman, changing in harmony with the themes in the dreams of the narrators. In this way, we notice that while what is inside flows outside, the longing for the life outside permeates the “innermost,” namely, the dreams. The film juxtaposes at a doorstep these two spaces seemingly separated by a balcony, erasing their difference in the tunnels of the unconscious.

Watching the everyday happenings on the street, we notice that most of the dreams played out on the soundtrack share common patterns. We hear that those with revealed longings for being in crowds are afraid of contact in their dreams, or that the fear of the virus haunts people through images like entering a room full of bats or kissing a crocodile. Apart from such representations of the fear of the pandemic at an unconscious level, we see that the traces of social traumas or political pressures accumulated in collective memory are also among the common themes of the dreams. Another film addressing collective memory in a similar way is The Lightwell by Begüm Özden Fırat. The film invites us to rethink sounds within spatial confinement through the lightwell of a building. It focuses on the experience of maintaining public life under lockdown conditions, contrary to periods when urban life was mostly experienced in public, inviting us to observe the relationship between sounds -accumulated at the lightwell- and spatial belonging. The film seeks answers to the questions of how diverse social groups relate to each other through sounds, which sounds are thick, which sounds are dominant, which sounds are not heard at all or how neighbors hear each other. Fırat starts the film with an image from her camera fixed at a position to face the lightwell of the building. Afterwards, we look at the lightwell from different angles at different times and hear the sounds, trying to predict to whom they belong. At the live conversation,the director said that before the pandemic she also heard various sounds from “inside” through the lightwell, but they intensified during the pandemic, and sounds from “outside” also entered the scene in several ways. While reflecting on how to view images through sounds, and editing together previously recorded sounds and images, the director spotlights the sound sphere as a sphere of struggle.

As we see the lights and darkness emanating from homes through various angles, we notice that routine sounds (dishwashing, showering, conversations at home etc.) and public sounds start competing against each other. In my opinion, this is what makes this film so unique. Calls to prayer and mass applause in support of health workers get mixed up in the lightwell. The film portrays the encounter of the worldly and the spiritual, those at the bottom and those at the top, in Fırat’s words. Later on, at the carnival scene where routine sounds join the struggle, the director uses split screen – a stylistic choice to visually reflect this cacophony. The moment we feel that we are losing touch with the auditory reality, the visual structure follows the same effect. All of a sudden, myth and reality, dreams and materiality get intermingled. The film once again reminds us the relationship between auditory sphere and public sphere. Sounds interweawe their own language and convey commonalities, controversies and structures of belonging. The Lightwell is also a unique title in the programme for representing what is eliminated and what is monumentalized in collective memory. There is a struggle that is played out through sounds pointing to the role they play in constructing memory.

The last film I want to analyse in this section is Haydar Taştan’s Street Solidarity, which focuses on a particular example of living outside – one that is unfamiliar to most of us, swaying between the concepts of inside and outside during the curfew. The film focuses on Kadıköy Solidarity Network, an organisation helping people living on the streets or having difficulty accessing staple food during the lockdown. The motto of the solidarity network is “Say yes to physical distancing, say no to social distancing”. It affirms how solidarity practices can help maintain mental and emotional health, by overpassing the grip of the lockdown. We see mostly empty streets, occupied only by solidarity volunteers and those in need. The film spotlights the corrupt system that differentiates between lives “worth living” and lives “dispensable”. It also exposes the reality of lives rendered unknown. Using the language of solidarity as the basic language of the narrative, Street Solidarity keeps record of erasure (not that of forgetting) and makes us notice that we do not even remember what we have forgotten. While there seems to be no emphasis on memory in the film, in my opinion, as Taştan zooms in on erased lives, the film makes a statement about collective memory. While collecting images, the filmmaker chose an observational mode. The documentary uses a language that puts forth a plea for equality and solidarity, depicting everyone as potential actors in a solidarity network.

THE CITY BETWEEN REMEMBERING AND FORGETTING

If remembering does not simply denote recalling lived experience from memory, forgetting cannot be simply ceasing to remember what we have encountered in our lived spacetimes. In fact, we do remember and forget what we have never experienced -in the name of those with whom we have shared the same space at different times. This is probably the fuel for our memories. Forgetting, as well as remembering, is stored in time and space by being both divided into and multiplied within crowds. Daring to turn one’s eyes to this repository brings about a perception of history in which the past and present are viewed through dual mirrors, rather than a linear flow.

The video-collage Ghosts of the City by Fatih Pınar presents such dual mirrors and takes us to spaces of memory. Pınar’s “camera-eye” zooms in on Taksim Square and its side streets. He strolls through the corners of our memories. He leaves us with the footage of these streets filmed in June 2013 filled with crowds, namely the Gezi Park protesters, and in 2020 completely deserted due to the lockdown. Yet, instead of presenting these periods chronologically, Pınar constructs an intriguing conversation between image and sound tracks – the sounds of the past echo on images of today’s deserted streets. This juxtaposition refers to the dichotomy of remembering and forgetting. While we are watching a day footage of Mis Street during the Gezi Park protests, we suddenly face the sharp silence of the same street in 2020, as if it were the night of that day back in 2013. The next sequence includes voices from 2013 on the image of empty streets, in a dream-like moment. The video footage from the Saturday Mothers2 gathering at Galatasaray Square, is followed by the voice of a woman reading aloud a declaration – this time in the noiseless void of the square. Editing together the memories of social struggles, Pınar is looking for a cure for the rising anxieties regarding the future in today’s abandoned spaces of the city laden with memories of collectivity. With its focus on the shrinking or changing spaces of social struggles, Pınar’s film can be seen in conversation with another film in the series: Remember the March by Güliz Sağlam.

In this film, Sağlam questions the widely-used catchline “Stay Home, Stay Alive” that has been echoing in our ears throughout the pandemic. The director chooses to focus on “women’s experiences of the pandemic”. We know that the performance of femininity as a social construct is linked to “staying home”. However, with the lockdowns, the meaning of being home for women has become more and more aggravated because all the members of the household are now home. Now that the perpetrators of violence are always home, there has been a noticeable increase in cases of domestic violence and domestic sexual abuse since the outbreak. To highlight this issue, Güliz Sağlam mixes women’s statements from the May-June 2020 reports of Mor Çatı Women’s Shelter Foundation on voiceover. The video footage of an “ordinary” day outside is accompanied by voices reading statements that disclose acts of violence. This aesthetic choice lays bare the horrendous fact that violence has become the everyday reality of countless women during the lockdown. The film ends with images from the Women’s March demanding the immediate enforcement of Istanbul Convention and the implementation of Law No. 6284. This is celebrated in the film as an exceptional moment: At a time when silence rules the streets, women continued raising their voice against the normalization of violence. “If you fall into despair, remember the crowd!”3 said one of the banners in Women’s March on March 8, 2020 and this slogan got inscribed in the collective memory. The film also emphasized a dilemma that underlies the “Stay Home, Stay Alive” catchline. For women, staying home does not mean survival. Through the images of women chanting on the streets, where their common memory has been constructed, the filmmaker reminds the viewers how women reclaimed the public space to make visible the violence behind the closed doors. For women on the streets, and for viewers watching these impressive images, remembering develops an identity in a way. Being a witness acquires historical agency through remembering and reminding.

While the lockdown has created a general tendency to encode the past as a nostalgic and comfortable zone, one must insist on remembering the debris and ruins that it holds.

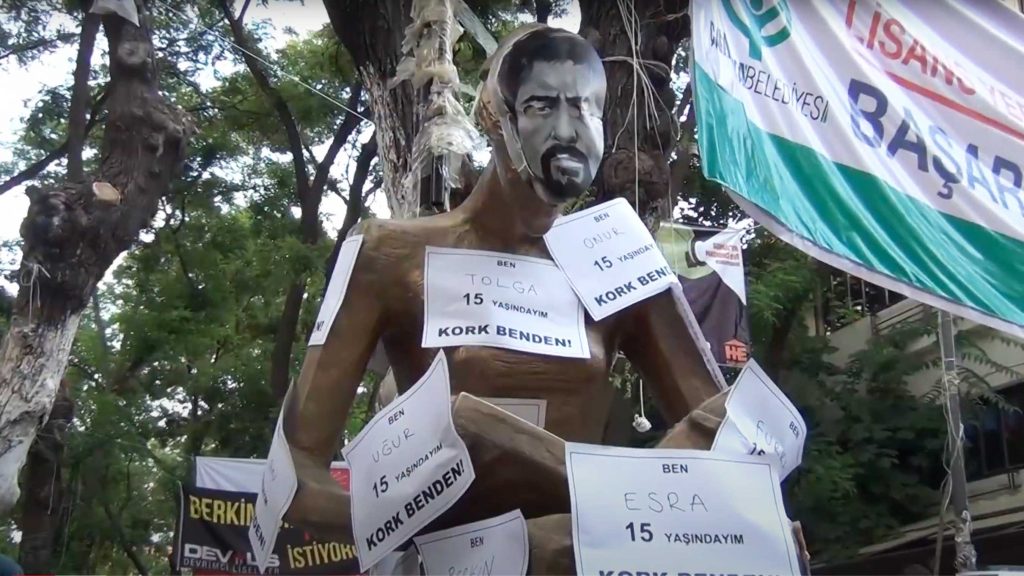

Last film I want to focus on here is The Statue by Sibel Tekin, a member of Seyr-i Sokak video-activism collective. This film looks back at the urban struggle in Ankara. It is a diary of video-activism created by editing together raw footage filmed between 2013 and 2020. It traces the collective memory through urban experience. In this film, the space is a witness. Here, the Human Rights Statue on Yüksel Avenue reminds us of the statue in The Balcony and Our Dreams. However, this film points to the representative status of the statue regarding collective memory.

The footage shows press announcements read in front of the statue on Yüksel Avenue. This statue has a key role in the history of the city and its collective memory (with positive connotations for some and negative ones for others). It is the usual gathering place of protests in Ankara. In ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’ Walter Benjamin cautions about the violence that underlies the history of cultural treasures, such as monuments. Without exception, cultural treasures have an origin that cannot be contemplated without horror. “They owe their existence not only to the efforts of great minds and talents that have created them” writes Benjamin, “but also to the anonymous toil of their contemporaries.” With this, Benjamin points to how cultural treasures, such as monuments, curtail history. This is the idea that underlies his famous statement: “There is no document of civilisation that is not at the same time a document of barbarism.” Monuments, through the process of monumentalisation, are made to forget more than to remember. History is recorded in the name of the victors. As they capture the spoils and leave, the monuments they leave behind are not only reminiscent of their victories, but they also help erase the traces of the defeated. Behind all that splendor is not only victory but also debris. Looking back at the film through this perspective, we see a counter-monumentalization or a move towards recovering the debris, in which the function of monumentalization is destabilized. While the erasure function of the memorial is turned inside out, we view an urban struggle that embraces the possibilities of remembering. Collective memory is reconstructed as a moment of encounter.

IN SEARCH OF NEW STYLES

Although all the films in the series address a similar question, it’s possible to see some clusters in terms of stylistic preferences. Looking for these similarities in narration might shed light on potential affects that the series aims to generate. In this section, I will analyse yet another cluster I see in the series. These three films establish a narration inspired by the power of literary forms, such as oral storytelling, poems, and epistles. They thus incorporate intuition as a method to comprehend the complexities of inside versus outside. The first film I want to discuss is Inside by Elif Ergezen.

The title of the film connotes not only domestic isolation but also solitary confinement. Ergezen’s film interweaves the private spaces where we feel imprisoned with confinement cells, quoting from the letters sent ‘from inside to inside’. In voiceover, she reads the letters she received from her friends on hunger strike. The emotions evoked by the fragments are conveyed through a collage of visual recordings from the inside and outside of house and images from her favorite films and poems. The film can be seen as a call for justice and freedom, as the director says that thinking about when, how and under what conditions our lives can be worth living is as essential as thinking about the issue of health under the challenging circumstances of the pandemic.

The second film I want to discuss in relation to Ergezen’s impressive documentary is Walking the Streets of Diyarbakır, which relies mostly on the poetry of epistles penned in Kurdish. Özkan Küçük’s film is an elegy for the destroyed district of Sur and its stolen future. Küçük brings in the footage from an unfinished project: Strolling through the labyrinthine streets of Sur, his mind wanders about the memories of destruction he witnessed, conveyed via voiceover narration. The images of Sur before it was destroyed thus become a lament for what it lost forever. In the live conversation Küçük said that he found it extremely hard to face the full destruction of Sur, not even to be able to film it. With the entire city and its memory wiped out, the newly-shot images fail to convey the burden of witnessing and mourning such a destruction. Küçük resorts to symbolic tools such as the images of an earth-mover to connote destruction and displacement, and the photographic images of the inhabitants to encapsulate their everyday reality in the city, now ruined forever.

The search for an innovative style is most evident in By the Shadow, directed by brothers Yiğit and Efe Durmaz. This film constructs its narration via a combination of image and text. The directors started to shoot videos at home on a daily basis in order to overcome the boredom of the lockdown. In time, they realized that the texts they wrote for these videos sounded like a fairy tale. As the tale grew, to their surprise, they thought it reflects the current state of mind, living through the pandemic and post-truth era – marked by the blurred boundaries between myth and reality. The directors took inspiration from our puzzlement, face-to-face with a reality that we find hard to navigate. The film builds up on this feeling of confusion and uses ‘shadow play’ as a metaphor to comment on distorted realities and borders of inside versus outside.

Next I want to mention The Bat Bird by Gökçe İnce. A mix of various genres, the film has a fairy-tale-like narrative, just like By the Shadow. However, rather than a fairy tale, which is the product of a more established oral tradition, it quotes hearsay about bats that were displaced due to dam construction in a village in Balıkesir. It uses a semi-mythological narration, quoting the villagers talking about bats, but the film’s power is not limited to its creative use of these oral storytelling styles. As the director explained in an interview, it comments on the co-existence of humans and other creatures from a perspective that does not privilege or prioritise the human. Against the anthropocentric and self-centered narratives of the lockdown, The Bat Bird spotlights the myths that fuel fear. With its message, it can be seen as an attempt to erase the differences between species – as it’s increasingly agreed that human privilege is both the perpetrator and victim of ecological disasters.

Finally, I want to discuss On the Wings of the Butterfly, depicting the daily routine of the director İlham Bakır as captured with his mobile phone during the lockdown. This film differs greatly from the others with its narrative and theme. While the other films focus on the contact that the inside establishes with the outside, this film deals with the difficulties in work life caused by the lockdown. It also conveys how communication between family members is affected by the exploitation inherent in this new working style. Including his daughter and his teacher wife in the shooting phase, Bakır reverses the arguments that frame staying home during this period as a class privilege. The film treats the issue instead as part of the exploitative nature of flexible work that goes beyond the concept of working overtime. It reveals that the pandemic drags people working at home into burnout, and the communication problems it creates within families further aggravate the emotional effects of the lockdown. While the film was mostly shot in the house, Bakır makes a different stylistic choice and records his daughter’s tantrums using camera angles reminiscent of a horror movie. This short film skillfully presents the dominant mood during the pandemic via a somewhat humorous tone.

Looking at all these titles as a whole, it’s possible to chart out three main clusters of emotional and intellectual engagement with the lived experiences of inside and outside during the lockdown: the melancholy of the past, the catatonia of the present, the eerie unpredictability of the future. Even though the lockdown has brought a tendency to encode the past as a nostalgic and comfortable zone, in order to overcome the obscurity of the future, one must insist on remembering the debris that is waiting to be rescued. Perhaps for this reason, all the filmmakers recording the present, seek a remedy for the uncertainties that it holds. Delving into memories as well as oblivion becomes a tool for survival. What unites the filmmakers in this series is their quest for the echoes of the silenced, in everything we see and hear, at this point in time at this place on the face of the Earth.4

NOTES

1 After the premiere of each film, live conversations were held on Altyazı’s YouTube channel (in Turkish), where a film critic from Altyazı interviewed the directors, followed by a Q&A session.

2 Editor’s note: A group mainly consisting of mothers whose children are victims of forced disappearances, ‘Saturday Mothers’ stages weekly sit-ins to raise awareness for forced disappearances and demand justice for political murders in Turkey. On Saturday, September 26 2020, the group held their 809th protest at Galatasaray Square. Another group around similar political action is Argentinian ‘Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo’.

3 Editor’s note: The film’s title, Remember the March, references this slogan. The filmmaker swaps here ‘the march’ for ‘the crowd’ in the original banner, bringing to mind the impressive Women’s March on March 8, which is celebrated as International Women’s Day in Turkey.

4 This article uses fragments or develops some ideas from previously published pieces by the same author on the website Kroniko.