“The camera does not lie.” But what about those who control the camera? Video-activist and documentary maker Oktay İnce, whose film Nothing Outside the Frame we showed in our From Below series, tried to answer this and other questions in his articles series on Law and the Image, which he wrote in 2013. We are publishing a selection from these articles as part of our series.

Text by Oktay İnce

Translated to English from Turkish by Sebastian Heuer

Since images can be manipulated, falsified, or even created out of nothing, courts used to view them not as definitive legal evidence, but rather as a matter of opinion. It was only after criminal technologies became refined enough to precisely dissect edited images that photographic images and video footage gradually evolved into central elements of trials – and of course, after the media had furnished images with a persuasive force vis-à-vis the public.

The image became the core element of legal processes after the state developed into a giant surveillance mechanism that watches over the streets, people’s homes, and all other spaces, whether they be open or closed. This mechanism serves to identify the perpetrators of crimes against the system or to deter them from committing crimes by spelling a constant warning: “You are being watched.” In modeling its surveillance mechanism, the state did not content itself with city surveillance systems, the so-called MOBESE cameras, but also established “Photo and Film” centers and sections in all police departments and increased its technical capacities and personnel. Now, the photo and video units of the police, which consist of at least five people, are recording even the smallest commotion in the streets. This “setup” is complemented by the fact that courts are equipped with screens for video display and video-conferencing tools to hear remote witnesses, while lawyers present their defenses in front of a screen and cameras even record the courts themselves. Photographic and video records are no longer used only for the identification of perpetrators, but also as official evidence for their conviction in the courts.

It has become almost impossible to think of evidence without visual images. Due to the persuasive force of video and photography, the event, which witness accounts could only try to visualize somehow, can now directly be shown: “Here it is, this is what happened.” As an imprint of reality, the image has become a means of evidence equivalent to fingerprints.

The good thing about this is that the state itself gets caught in the monitoring and recording networks it has established. The requirement to keep image records in prisons and police stations, the most isolated places of state torture, was instrumental in preventing torture or punishing its perpetrators when it occurred anyway. Think of the Engin Çeber case and many others… Those who killed Ethem Sarısülük and Ali İsmail Korkmaz were identified and sentenced for their crimes thanks to street camera footage. The identity of the policemen who killed Nihat Kazanhan was determined based on the images recorded by the armored vehicle from within which he was shot. To determine which police officer was responsible for shooting lawyer Tahir Elçi, the footage of the incident is analyzed second by second.

As an imprint of reality, the image has become a means of evidence equivalent to fingerprints.

The notion that “cameras are everywhere” may be a deterrent for activists who do not want to be caught by the state after committing a crime – but so it is for the state’s law enforcement agencies who are concerned that images of their actions might surface the next day, exposing their conduct, if not leading to their conviction. Thus, the omnipresence of cameras operates as a mechanism of self-control for the state itself. Where a camera is watching, the dose of state violence decreases. In some countries, the task of recording is no longer entrusted solely to the police’s photo and video units. Instead, every police officer is equipped with a body-worn camera and the complete recording of operations has been made obligatory. Where the camera is involved, surveillance and control go hand in hand. During demonstrations and protests, the photo and video section of the police monitors the situation through the surveillance cameras on the streets.

While the surveillance cameras record the perpetrators so that they can be put to trial, they also direct the operations carried out to control and disperse demonstrations and to catch those who are hiding. In fact, while the armed clashed in the Sur district of Diyarbakır continued, bombings were carried out according to images transmitted live from unmanned aerial vehicles.

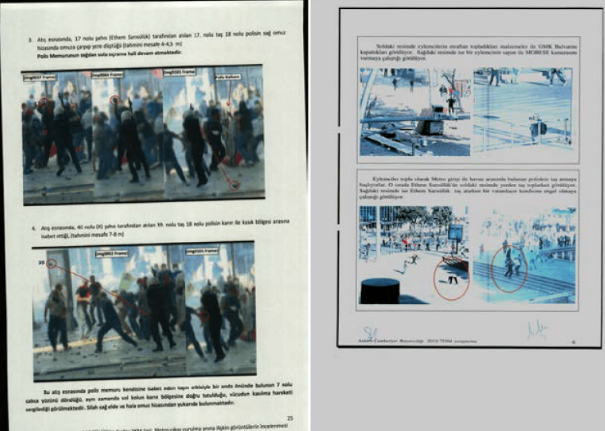

How does the image transform when it becomes part of legal processes and is subjected to legal procedures? The first thing we notice is that video images are slowed down or frozen, turned into photographs. The speed of images is reduced so that the naked eye can see the details. Moreover, certain moments in a video sequence or particular spots in an image are marked and circled: “Here it is, right there, that’s it.” The recordings sent to the courts by the police are not submitted as raw footage, but as edited material. Although street cameras also record sound, the recordings sent to the courts are often silent. During police interventions, the police either turn away their cameras to avoid recording those moments that may be used against them, most importantly the sounds, or such sequences are cut out later during the editing process. When a MOBESE camera accidentally captured the moment Ethem Sarısülük was killed by the police, the camera immediately turned its eye to the sky and did not look back down onto the square until the murderer was out of sight.

Following the prohibition contained in the Code of Criminal Procedure, it is usually not permitted to create audio and video recordings in the courts. Although trials are held in public, the courts are “off the record.” Until a decade ago, the courtroom was a theater stage where any recording was strictly interdicted. Today, the courts are both theater and cinema. The court panel is both on the podium and on the plasma screen, which is also used to display the “polifilms” which are edited and manipulated versions of the recordings made by the Police’s Photo and Film sections – that is, recordings created not by MOBESE cameras but manually.

The image does not only show where and how an event occurred and who was involved in it, but technically can also indicate when it happened. By matching the movements and time frames of digital recordings taken with different cameras and from different angles one can try to get to the truth of the event. In cases where the police are the perpetrator, they choose to submit edited material rather than raw footage to the court in order to obscure when and how the incident went down. Here, we can think of the 13 seconds clipped from the video showing the killing of Tahir Elçi.** Since metadata concerning the date of creation or modification is inscribed in raw footage, an academic from a Radio, Television and Cinema department is likely to be commissioned as an expert to analyze this data.

No trial seeks the truth, every trial seeks to prove its thesis. Or let’s put it this way: What truth is pursued depends on who needs a certain truth at a certain moment. This largely determines the nature of the “forensic montage” crafted by the Photo and Film section of the police, that is, the parts of the video footage included in this film. For example, the photographs included in the crime scene report on the killing of Ethem Sarısülük were arranged in such a manner that they presented minute evidence of just how many stones Sarısülük had thrown at the police in order to substantiate the thesis that “the policeman had to shoot him.” Likewise, a sequence of 13 seconds coinciding with the moment lawyer Tahir Elçi was shot were clipped in the montage and it was claimed that at the moment the shooting took place, the police had “gone off the record in surprise.”

The “polifilms” prepared for the court include image material that shows that the police made their announcement before intervening in demonstrations, that detentions were conducted according to legal procedure, and the weapons confiscated. The state is under the constant obligation to prove that it remains loyal to its own laws. In addition to making films, documentarians act as forensic experts, officially carrying out technical analysis to establish the reality of the incident under scrutiny by diving into the details or dissecting the montage of the videos submitted as evidence.

Meanwhile, when psychologist act as experts they rely on video footage of the incident to analyze the mood of the perpetrator or victims in their reports: “When the protesters saw that the policemen was holding his gun in his hand, they seemed startled and afraid and started to run away.” Or: “The policeman who was holding his gun in his hand was enraged, kicking a demonstrator before firing his gun.” It is not only the state that can harness the legal power of the image as a means of surveillance, control, display, and evidence. Provided that we have mobile phones, we all hold this power in our hands. If the bombing of the Umut Bookstore in Şemdinli in 2005 had not been recorded on a mobile phone, it would not have acquired the status of an event that actually happened. In a similar manner, the state tried to obfuscate its role in the murder of Tahir Elçi in November 2015 by clipping 13 seconds from the footage of the incident.

“THE CAMERA DOES NOT LIE“

Let’s dive a little deeper into these questions and think about the relationship between law and images, which has tilted in favor of the image, about the ways these two concepts affect each other and about how their interaction transforms both.

Today, the testimony of the image has replaced the living witness. Where a murder committed by the state or any other legal person is concerned, the question “Do we have any images?” has become more important than the account of any human witness. Ever since the first trial took place in history, the juries, whether it be the church’s inquisition or the Ottoman qadi who adjudicated according to the rules of the Shari’ah, tried to make sure that witnesses told the truth and acted objectively. But human beings were unreliable after all. They would tell the truth at the police station, then deviate from their account at the court. In order to guarantee the veracity and objectivity of testimonies, witnesses had to put their hands on holy books or sometimes, as in various European countries, it became a moral imperative to refrain from lying while giving one’s testimony. It is thanks to camera footage that the veracity and objectivity of testimony are more or less secured today.

“The image does not lie,” because the machine that records the event is inanimate. The image it produces is “a trace, a copy, an exact mirror image of reality.” The testimony of the camera is seen as more convincing, more persuasive than a human being whose tongue easily twists and turns in all directions—because of bribery or fear or other interests. The accounts of human witnesses now gain credibility only after passing the test of the camera, that is, after being corroborated by images.

Images also introduce a form of public control of the courts and their judgments, which they render on behalf of the public. This is due to the fact that the image can reach and convince large masses and turn them into living witnesses. For instance, people watching the video of Ethem Sarısülük being shot by a police officer may be unable to reconcile the decision to acquit and release the defendant with their own conscience. In effect, the legitimacy of court decisions becomes contested.

The thesis that “the camera does not lie” is of course relative, it is debatable. What is important here is what lies inside and outside the frame, the subjectivity of the image, that is, what the hand holding the camera focuses on. But if we want to find an answer to the question when the image lies or whenit does not tell the truth, we should leave aside the discussion about the manipulation of the image that happens during the editing process for a moment. Philosophers who have contemplated the question of the truth of the image, like Ulus Baker, among others, have stated that the image tells “true lies”, “deep lies” and even “aesthetic lies.” But all these lies were the work of images that had been turned into films, no matter how marginal, of at least two consecutive sequences through montage. It is not the image that lies but us. The image has its own existence that is separate from ours. We could place a photo from Palestine in Kobani and a photo from Kobani in Cizre and it would most probably be convincing. However it is not the photograph that is lying.

In the lawsuit regarding the killing of Ethem Sarısülük, Prof. Dr. Klaus Stanjek from the Film and Television Production program of the Konrad Wolf Film University Babelsberg acted as expert documentarist. In cinema, 24 consecutive frames per second create the moving image. Stanjek detected that after the policeman who killed Sarısülük fired two shots into the air, there is only one frame in those 24 frames, in which the gun is pointed horizontally facing the demonstrators. Three frames later, Ethem is hit and falls to the ground. Stanjek also found that none of the stones thrown by the demonstrators had hit the police, thus refuting the state’s claim that the policeman had “acted in self-defense” based on the images.

When the camera is pointed at any given event, the image captured in its frame is but a fraction of the recorded reality: it is incomplete but true, it is what it is. During the shooting of Sarısülük, a CNN Türk camera focuses exactly on the scene, clearly recording how the murder was committed and thus answering almost all questions concerning the factual truth of the event. The state-controlled MOBESE camera, on the other hand, turns upwards and away as soon as its operator realizes what is going on, then our vision is clouded by the tear gas thrown by the police. However, the images in the frames of both cameras reflect reality, truth. There is a murder being committed and at the same time the scene is covered in a cloud of tear gas. The MOBESE camera does not and cannot say, “this policeman did not commit this murder.” The only thing it can do is to refuse to bear witness.

Each camera has a different angle. It is the combination of multiple points of view that creates a totality. Dozens of minor things are happening at the same time in that square. There are numerous cameras capturing each of these things from different angles. One camera only shows people from the neighboring shop who are looking at the square with panic and bewilderment. Another camera shows the live witnesses of the incidents. Meanwhile, the demonstrators in Güvenpark are throwing stones at the police. An ambulance is approaching… All these recordings are true, they have a direct or indirect connection with the central event. They are only a fraction of the reality at that particular moment, but what they show is true. The ambulance was approaching, the demonstrators were throwing stones, the people in the shop were watching how the murder was committed, the policeman came running and shot Sarısülük. If in those 13 seconds the reporter of the Dicle News Agency had held his camera in the direction where Tahir Elçi was shot, rather than at the policemen who were firing their guns, we would have been able to find out more precisely where the bullet came from and how Elçi died. And yet, both pieces of information captured in the frame of the camera, which turns from Tahir Elçi towards the police, are true, are real.

As the camera becomes a witness, we see an increase in cameras and image production in the streets and at crime scenes.

The image’s property as evidence and its capacity to infinitely repeat any event are at work simultaneously. In the exhibition Aksinden Yankı (“Counter-Reflection”), we tried to show that the images presented to the court as evidence regarding the Gezi Protests by the Photo and Film Section of the Ankara Police also had the potential to reproduce the power of the protest movement. We did that from perspectives that news or video/activist cameras can usually not assume, using images recorded from above by the MOBESE cameras and from the opposite side of the protesters by the hand-held cameras of the police.

Some events are only recorded by the police, the public does not have any image of them. The people, whose conscience and opinion are one of the founding pillars of the courts, are thus deprived of the image. In the murder of Nihat Kazanhan, for example, the state was forced to submit the images in its possession to the case file from there they spread to the public. With its ability to infinitely rearticulate the moment of Ethem Sarısülük being shot, the image ensures that the case will never be closed. Not forgetting and not letting anybody forget, it tirelessly refreshes the memory of this event for the future generations.

As the camera becomes a witness, we see an increase in cameras and image production in the streets and at crime scenes. Installing street surveillance cameras wherever it can, the state expands its surveillance and control mechanism beyond all estimates. And if we think of sound as an image, we can also view wiretapping as part of this mechanism.

However, the camera is a tool that serves those holding it in their hands, observing the person in front of them. As citizens, those who suffer injustices at the hands of law enforcement officers turn the camera’s controlling and surveilling lens on the state so that the latter sometimes gets caught red-handed by the systems it established to surveil the people. The private security camera systems set up by businesses, institutions and individuals give us an indication that image production has exploded beyond the wildest dreams. Ultimately, we are faced with a gigantic repository of images produced as the state records the people and the people record the state and themselves. Today, YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, Vimeo, etc. compel us to make this production visible and accessible to the public.