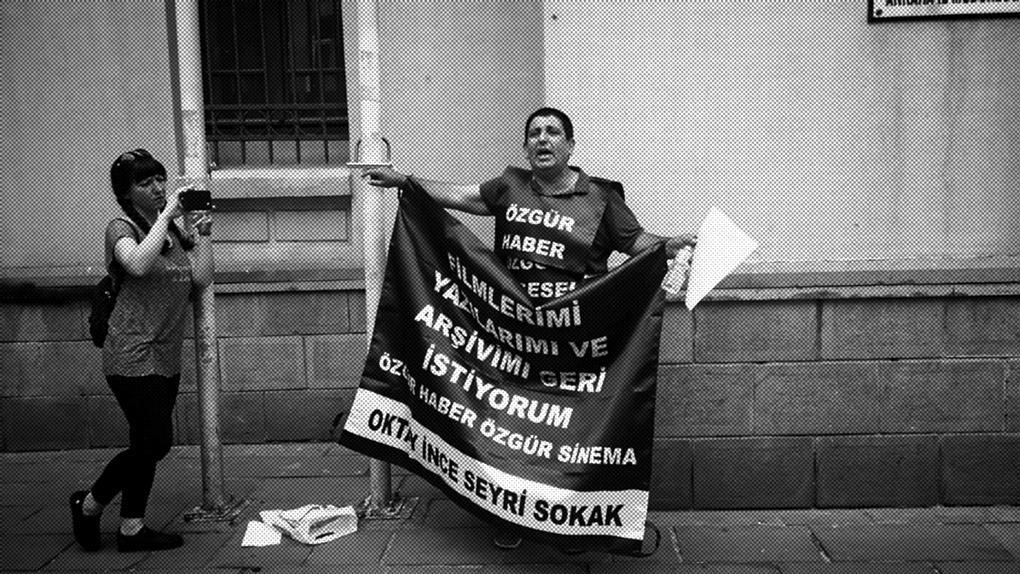

Oktay İnce is a moving image activist, an image worker. He has been involved in and co-founded several video-activist groups in Turkey including Karahaber, Seyr-i Sokak and Artıkişler. On Tuesday, Oct 16, 2018, the house of İnce was raided by the police and his 20 years of work were confiscated. He began protesting to retrieve his archive and was taken into police custody several times.

In this text he wrote for our Speaker’s Corner, İnce shares his political and ethical perspective on production, (dis)possession and circulation of images.

By Oktay İnce

I’m a video-activist, documentary maker, and videographer. I’m a slave only to reality. The only law I am subjected to is the law of reality that is waiting to be seen and shown, not the law of the State. My blinding shame is the reality that I have seen, but ignored.

I am aware that my own self-censorship is fed by my fears and concerns about losing my fragmented comfort. I am not going to nourish it, because my existence will lose its meaning if my eyes and words are not free.

No state law can question why I record images or make films. I reserve the right to my own artistic vision and only according to my own ethics and through common sense. I reject any external force and pressure from the state or the capital. I carry out my practice based on the principles of my freedom. This freedom, though it may be the need of independence from negative external conditions, is essentially my own internal freedom in terms of pursuing my own vision and standing my ground.

With the request of the prosecutor and the approval of the court, police raided my house on October 16, 2018 and seized all my films, writings, projects, raw footage, my entire archive, that is, my cultural labor of the past twenty years. This raid came after a police investigation that began based on a tweet sent from the account of our video-activist collective called Seyr-i Sokak, which did not use the term “terrorist” when referring to the two murdered militants of TIKKO (Liberation Army of the Workers and Peasants of Turkey), thus we were accused of “making propaganda for a terrorist organization.”

What is terrorism? Who is a terrorist? Every power defines its own terrorist.

As a documentary maker, I cannot be bothered and concerned with these relative and changeable definitions. We, as video-activists, have our own concepts and perspectives to expound the issues. Using the same language of the power or the state or the capital, and nestling up to the point of view of any such power take us away from our core.

Anything that moves a leaf on earth is in the same category for us as the actors of an event. They are the makers of reality. They are the creators of events. They are the causes of events. The good and evil are the same, as realities, because they both exist. Each form is not only the carrier of its own content and function, but also an invitation for a certain perspective. Through our own perspective, we record everything that is clearly visible out there and we show everything that can be shown. We speak with the concepts of cinema and art, not with the restraints of social or political authority. Whoever defines or is defined by it, “terrorist” is not a cinematographic concept. If we turn it into a cinematographic concept, it certainly won’t have the same implications as the state’s definition of it. For instance, let’s say: “We are the terrorists of image.” We may lay landmines to all the fields of meaning with the chaos and uncanniness of images.

18 hard drives and 41 DVDs that were seized by the state now became part of another story as hostages, prisoners, or leftovers, or as images whose freedom we struggle for…

All the images, documentaries, news, video-acts, video-arts, raw footage I had in 18 hard drives and 41 DVDs that were seized by the state had already their own stories. Now they became part of another story as hostages, prisoners, or leftovers, or as images whose freedom we struggle for, as images with the potential of putting people in prison —people who recorded them, people who couldn’t protect them from the state, and people who are recorded in them—, as images with a function we have never assigned to them, and as evidence to our “crimes.” No montage or any other narration of these images constructed after they are freed can exclude this narrative. Is this the price? (Of what?) We will see who will pay it.

The question “What could I risk to get them back?” can only find a meaningful answer for all of us when brought together with the question of the place where these images themselves occupy in the existence of this cultural labor.

The void is something you can see when you lose it, when you feel the searing pain of the possibility for no return. This is exactly it: Did you with your own practice create an external pragmatist relation with those images, or did you make these images part of your internal existence? Did you lose yourself by losing them? Imagine a state official saying, “you are still young, you can have another baby” to all the people who lost their children in an accident when a fast train runs off its track. Could I say “I can make another film, what’s the problem, as long as I do not end up in prison”? There is no negotiation!

We are trusted depositories of people whose stories we borrow. The answer for “To whom these images belong to?” is quite clear: “They belong not to the recorder, but to those who are recorded.”

The ethical responsibility of documentary filmmakers is not only a responsibility to retain self-respect for themselves and their practices. We are trusted depositories of people whose stories we borrow. The answer for “To whom these images belong to?” is quite clear: “They belong not to the recorder, but to those who are recorded.” I am in deep agony especially because these images are handled by those to whom we did not give permission, and some evil eyes will be touching these images to whom we did not give consent.

It is more bearable for me to deal with the possibility of legal prosecution or imprisonment because of any of my documentaries, video-activist works, or writings since this would be an external penalty. I had to start off with my protests especially and exactly because of the people who entrusted us with their stories, images, and voices. I feel that every risk I take in this path will increase the value I give to all these things entrusted to me.

It wouldn’t be far stretched to say that we started off with the motto, “from the image of the action into the action of the image” and “we have the experience of protesting through our 20 years long video-activism and documentary practice.” Our cameras, frames, hands and eyes, and our bodies with all of the senses and ideas have taken shape in accordance with this experience. We call ourselves as videographers or video documentary-makers, not as filmmakers. Let us mention Ulus Baker1 here as there are theoretical nuances on this issue. We have one foot in video-activism as independent reporters, and the other in documentary filmmaking. When I started protesting, my slogan was “free news, free cinema,” and the phrase “free cinema,” more often than not, gives me the feeling of taking shelter into a relatively more conformist and elitist space. We also sometimes call ourselves “image workers” which refers to every single bit of work done with moving images. Cinema, video documentary, or video-act and video-art — they are all different paths of treating and working with moving images.

Our theoretical discussions and different practices on the differences between video and cinema would have continued. However, when I took the public space for protest, what the listener understands became more important than what I say. Naturally in public space, the word “video” is no longer perceived as a distinctive method of creating work with a particular way of thinking; instead, it is perceived as moving images “recorded and shared” by anyone, including the listeners. And yet cinema is still the only concept that publicly defines and represents artworks created with moving images.

How can cinema resist, with what? I noted these words when I started: “Cinema can use all the possible ways of resisting, not only with the tools of cinema, but also with stones, slogans, and all the tools of protest used by implicitly or explicitly oppressed people.” Yes, but cinema can also resist by just “keeping on making what it makes.” Today, the documentary makers, who continue doing what they have been doing, and do not want to damage their relationship to their ethical values, perceptions, truths, and realities, are on trial.

My voice may or may not reach to other documentary makers, image workers, or gradually become a collective common voice. However, I keep on trying to talk with video-activists, documentary filmmakers, and all the workers of moving images with our own concepts. Yet I do not discuss video and cinema with the state. I struggle against the state, which deems proper oppressing us like this, with every tool of resistance left by the history of the resistance of the oppressed, and through relying on the whole tradition of struggle. At this point, this is an ethical and political issue for me, not an aesthetic one.

Translation by Belit Sağ, Alper Şen, Öykü Tekten

NOTES

[1] Editor’s note: Baker (1960-2007) is an influential figure in contemporary political theory in Turkey, known for his work departing from the philosophy of Baruch Spinoza and Gilles Deleuze. His work within the autonomist collective Körotonomedya is a major theoretical resource in the fields of video-art and new media.