The camera has historically been a device “looking from above,” a tool of power in the hands of those in power. However, this aspect of the camera, which implies asymmetrical relations, has been put to the proof many times throughout the history of cinema. There have always been counter-cameras to challenge this language of power. Nagehan Uskan discusses the videos in our From Below series as followers of this tradition.

Text by Nagehan Uskan

Translated to English from Turkish by Sebastian Heuer

Watch the videos of From Below series here

With its From Below series, consisting of 11 videos, Altyazı Fasikül brings together counter-frames that focus on moments and areas that are left out of the dominant frame, and in which the observer often is the subject of the struggle.

Since the early years of the history of cinema, the movie camera, accustomed to looking down from above, has been the key instrument in a burgeoning of asymmetrical relations between the observer and the observed. Cinema is not only born as the moving image, for at the same time it puts the gaze and frames of individuals who enjoy certain privileges on account of their social position and freedom of movement in circulation.

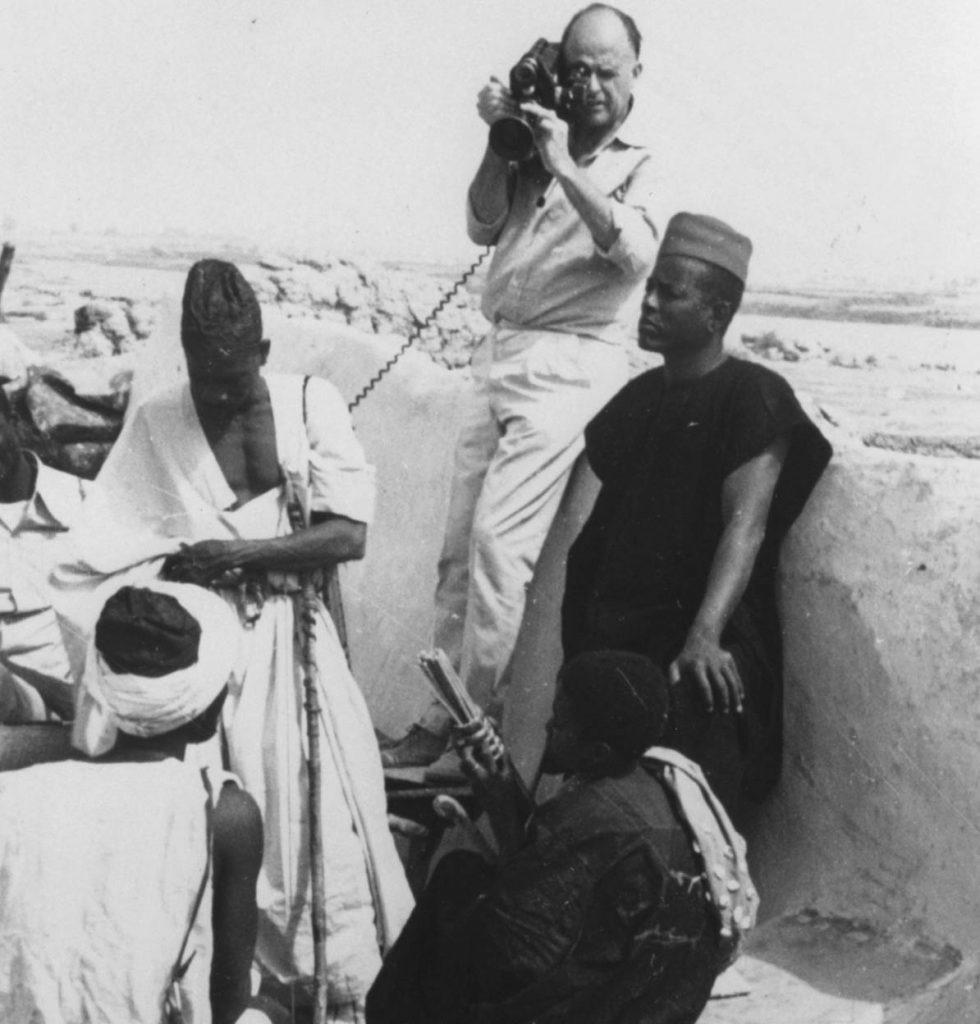

In the early period of cinema, the camera operators, who were travelling the world to collect images that would satisfy the expectations of their Western audiences, did what they could to make sure that their film strips most effectively transformed otherness into a spectacle. The camera was widely used as a tool of power in the colonies where, on the one hand, it controlled the exploited workers, while on the other hand producing distorted dominant images in order to justify the exploitation vis-à-vis the citizens of the colonialist countries. Jean Rouch, originally a colonial engineer, spared no effort to transcend his French identity and turn the camera into an effective tool for this endeavor. He was aware that he was looking from above when using a camera but did not see any need to hide this fact. He argued that reality would emerge precisely in a dialectical relationship that incorporated this view into its narrative.

The institutionalization of fiction cinema had the stories of great heroes take center stage in the narrative of Western cinema, while the story of those at the bottom had to remain outside the dominant frames and served as background items at best. Of course, since the early years of cinema, there have always been directors and film movements who thought that there were much more important issues to be recorded on camera. The first example that comes to mind is Vertov’s Lenin-supported documentary films…

Austrian Film Museum, Collection Dziga Vertov.

Backed by the agit trains, Vertov’s cinema mobilized the camera to weave a horizontal web between workers, farmers, and all proletarians on the road to revolution in order to make them aware of each other and convince them that transformation was essential. A horizontal network that rises strongly from below… another feature of Vertov’s documentary filmmaking becomes evident in Man with a Movie Camera. The camera is given the right to peep into every corner of the city, watching toiling workers as well as sleeping folks. Seeing better than the human eye, the camera must capture every moment of life and penetrate every part of it.

In Nothing Outside the Frame, Oktay İnce undertakes an extraordinary experiment in the style of Man with a Movie Camera. In doing so, he asks the people and animals he wants to record on camera for their permission and tries to discuss the ethics of the camera’s eye with them. His narrative includes the moments in which the people he films become suspicious of, avoid or shy away from the camera’s gaze. İnce draws attention to the director’s position of power in the relationship dynamics that define the frame, asking: “Objects, animals, children, the mentally ill, beggars… What are we supposed to do when we point our camera at those who are weaker than us?” A very valid question considering that throughout its history, cinema has turned the representation of the Other into a means of control and never hesitated to exploit its otherness to put it at the service of the spectacle…. In his video, İnce also challenges the camera of those in power by entering even those places that the latter cannot access. Carrying his camera to blind spots, he turns every moment into an opportunity to make the voice of resistance heard even from areas too dark for the lens to see.

The relationship between the documentary filmmaker and the subjects s/he captures is often compared to the relationship between hunter and prey. The documentary filmmaker is referred to as an image hunter: Just like the hunter targets and shoots his or her prey, the documentary filmmaker too is determined to choose and track his or her social actor and pulls the trigger of the gun (camera) at the critical moment. What Halil Yetiş is after in his Compassion trilogy is the behavior of the hunter on the scene. Despite being positioned next to the hunter and equipped with technical tools similar to those of the hunter, the way Yetiş holds his camera suggests that he is closer to the prey, even hunting the hunter, siding with the prey. He looks at the debate on the opposition between nature and technology from the side of the creatures which are most vulnerable to the power relations created by surveillance, the animals, and uses a technology usually in the service of power to serve those at the very bottom.

For his video Waiting for Hasan, Alper Şen chooses a recently filmed piece of war footage from the Syrian Archive and turns into a story. If the brutality of war cannot be represented, then how can we look at an aesthetics of war that is composed of images of abandoned cities and what can we add to it using our imagination? Hasan’s story is an opportunity to focus and dwell on, to really look at and reflect on one of the hundreds of images that have accumulated in the Syrian Archive. If preserving and archiving images is an action in itself in the face of the massive destruction of war, then selecting one of countless images to contemplate it takes this agency to another level. The direct encounter of two mechanical eyes, the momentary eye contact between the camera and the tank gun, is staggering. This moment has us witness a real-life copy of the fictional character from Edwin S. Porter’s 1903 movie The Great Train Robbery, who pulls his gun while looking us straight in the eyes, this time burning itself into our memories with a blast strong enough to blow the image itself to pieces.

Focusing on the Migros strike in Turkey, Aylin Kuryel’s video Side by Side takes the attempt to think with images to the field of workers’ resistances. Kuryel has us listen to Neslihan and Hüseyin, two of the subjects of the events, as they tell their own version of the strike based on four photographs. Initially dismissed because they had joined the union DGD-Sen and opposed unpaid leave regulations and other unfair working conditions, the Migros warehouse workers caused a sensation due to their lasting resistance that started in 2021 and their recent victories. What of this resistance remains as part of our collective memory?

Although photographs freeze and immortalize certain moments of grand resistances, this might not be enough. We need to sojourn in these pools of images, to reflect on these images and ask ourselves what they mean for our collective political memory. Through the photographs taken by themselves and other striking workers during the resistance, Neslihan and Hüseyin help us realize how important it is for the past and present of the memory of resistance to take our time to extensively look at and perhaps talk about these images. The things they talk about while looking at the photographs remind us that political actions is not limited to moments of protest, but that these struggles in fact continue when we reflect on them.

As an expression of a spontaneous and collective subjectivity, we see two hands recording the protests at Boğaziçi University against the appointment from above of a new rector that has been going on for more than 500 days in the videos Atlas and Witness by Osman Baran Özdemir and H. Işık, who are themselves actively involved in the protests. Özdemir and Işık virtually act as two collective eyes that permeate the entire resistance.

The images from different moments and periods of the protests that we see in Özdemir’s video at times progress in sequences that are reminiscent of mnemonic fragments and at times they leap across these sequences. Looking at these images, which are the product of a long recording process, we are able to reflect on the resistance and preserve its memory and to grasp its intersections with other resistances. These images testify to the strength that the resistance draws from its multilayeredness… The struggle for the university also recalls and certainly contains the struggle for the Istanbul Convention… The colors of the rainbow demonstrate the strength the resistance draws from its queer character, at the same time showing that the LGBTIA+ community’s insistence in its demand for freedom cannot be separated from the struggle to get rid of the “fake” rector. Özdemir’s video also focuses on police cameras. On several occasions, his camera comes eye to eye with more than one police camera, catching the observer in the act. It turns out that the camera, as a means of control in the hands of the dominant powers, cannot quite fulfill its function to surveil, record, and intimidate: There are countless counter-cameras opposing and by far outnumbering the cameras of those in power.

In Witness, Işık maps the campus of Boğaziçi University by crossing through its empty spaces. Meanwhile, we listen to the voice recordings of five different women who speak about the intricate aspects of solidarity. The women express an emotional vulnerability that even the cameras of protesters mostly tend to overlook amid the euphoria of resistance. While the video essentially shows a ghostly walk around the empty campus, its visual form does certainly not insinuate inaction. If, as one of the voices reminds us, there is value to knowing that the protests continue even when she is not there, walking around these places that carry the memory of the protests becomes an act of protest in its own right, even at times when these places seem deserted. This makes us feel that through their memory, the seemingly empty spaces contain much more than what appears at the surface. By getting together and talking about the different emotions that the resistance triggers in us, rather than living through these emotions individually, we are able to transform different experiences of exclusion into a new kind of strength and solidarity, thus adding a new and promising layer to our protests. Only a camera that dives down deep enough to get to the heart of the protests and is sensitive enough to listen and articulate even the fleeting moments of silence and shyness could tell this with such force.

In his video titled Untitled, Deniz Buga combines a photo series that has been in his personal archive for a while with a contrasting audio text. The different compositions of a group swimming at night in the summer of 2010 on the Tarabya shore are accompanied by a speech by Devlet Bahçeli in parliament on the pollution of the Sea of Marmara and the spread of sea snot. As we start wondering about these seemingly disconnected images and sounds, we come to realize that it is the Sea of Marmara that unites these two different texts. While the different frames that keep appearing one by one impose an abstract aesthetic on an ordinary moment of daily life, the political text, addressing environmental issues from a nationalist perspective, is just as surreal. Because Buga chooses to present his series of about 80 photographs without intervening in any way or without removing any of the images, he allows us to see how the photographer’s eye approaches the people it wants to capture and how it establishes a relationship with them. What he presents is not the one, the most perfect, the dominant image, which is selected from among dozens of photographs, but a wide range of countless successive images, with the lens sometimes sliding out of focus…

Deniz Tortum and Esen Tan take us on a tour to Turkey’s largest cinema archive at Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University, an archive that has been hidden behind closed doors and hard to access even for researchers and students for years. The video is composed of a quick succession of frames taken with a 360-degree camera, as if the camera wanted to waste no more time to introduce the audience to this place, which it was deprived of for so long… Obviously, our experience of this place, which has been a taboo for years, has to be virtual. Although this contrast between the impossibility of seeing the archive in real life and the fact that it will exist forever in the virtual environment may seem like a great contradiction, the act of documenting the archive constitutes a form of resistance against all attempts to make it untouchable. Through an act of archiving, the image of this archive, shunned for the sake of its protection, emerges from obscurity, preserved and recorded as an eternal image.

As an observed observer of state crimes, the newspaper Gündem was censored and shut down frequently, but came back every time to resume operations under different names. It is a testament to Kurdish history written from below. For a community that has faced constant attempts to ban and deny its language, literature, cinema, songs, and politics, Gündem is just one of the ways it has resiliently held its head up high. In an effort to reassemble and resurrect the newspaper’s banned archive, which the state has often tried to destroy, Fatma Çelik juxtaposes two types of materials in her video which is arranged as a collage. On the one hand, we have extracts from a Discovery Channel documentary about the printing and distribution process of a newspaper. On the other hand, different scenes from recent films about Gündem and the testimony of Zafer, who worked as a distributor for Gündem, offer an insight into what it means to flip through the pages of Gündem. In the face of Gündem’s struggle to survive, the production process of any newspaper under normative conditions seems almost parodic. The fact that Gündem still exists despite all efforts to destroy it is a political achievement in itself and it resonates with the experience of photographer Çelik, whose counter-memory has been shaped by this newspaper since her childhood.

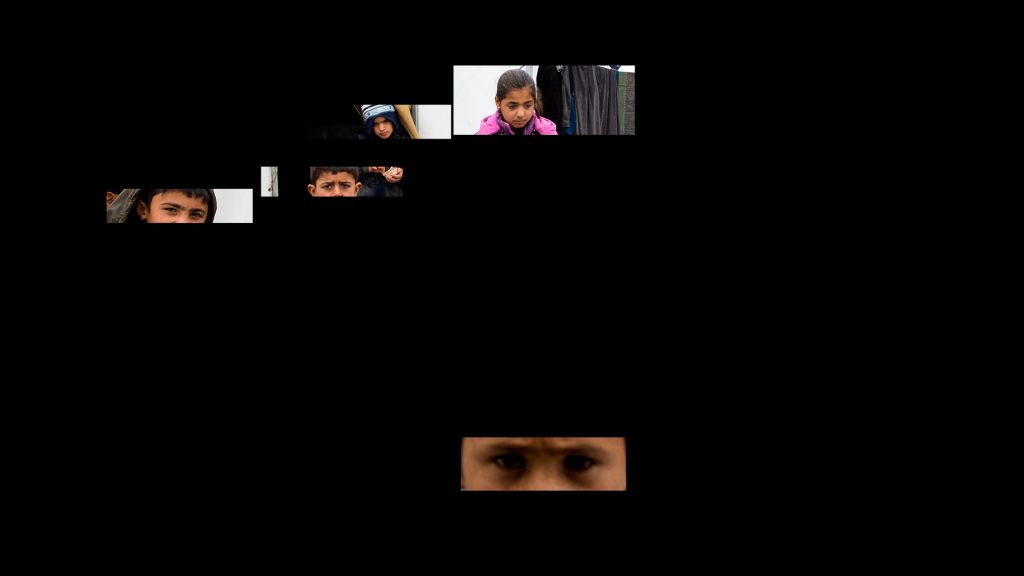

In Looking Back at Me, Aylin Kızıl, another photographer, performs a poetic reflection on looking, seeing, and being seen while looking, sometimes mixing her own voice with some of the unforgettable voices of recent Kurdish politics. She breaks up her photographs into small parts and fragments to amplify some of these parts, focusing on moments of eye contact, mutual glances, and sometimes missed encounters. Then, Kızıl unhides the rest of the frame, taking us to that area full of eyes and looks that we would perhaps have missed if we had not focused on these details before. This reminds us of the transformative effect the horizontal relationship created by a camera that is not identified with the dominant position or wielded by those in power but acts in collective empathy with those it looks at can have for both sides.

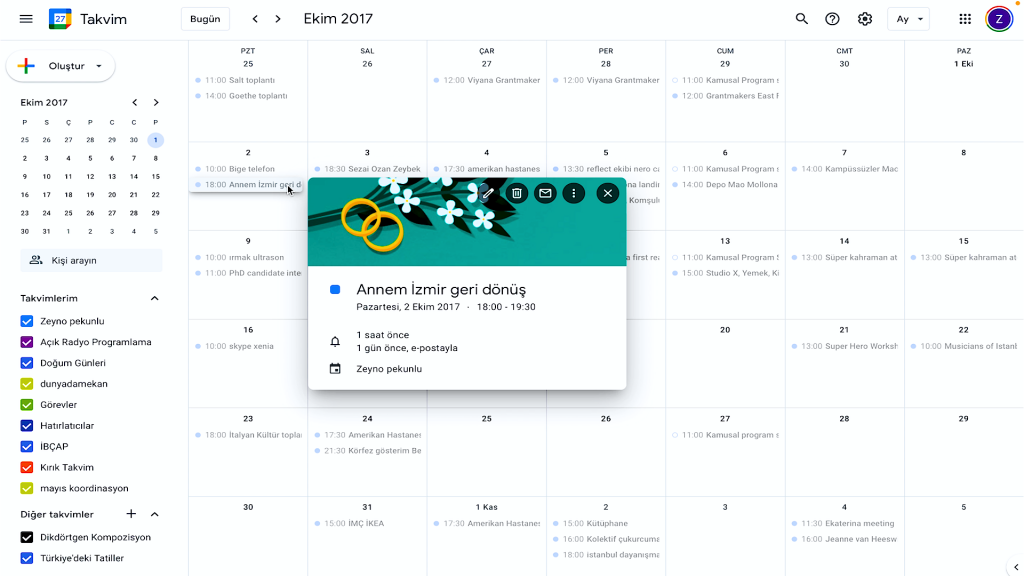

With their video I Am Watching You, Zeyno Pekünlü and Tatlıhan Tuncel take the issue of surveillance to another medium: social media. Every move we make in the digital sphere somehow turns into data for capital. This inconceivable data flow often inspires dystopian scenarios. Pekünlü and Tuncel take Facebook’s in-built drive to predict our consumption preferences and our lifestyle based on our calendars and turn it into a little game: Facebook ads are matched with events in a completely exposed Google calendar to stage a form of bingo or else, a humorous exhibit of the observation of the observer.

The videos in the From Below series not only weave a horizontal web from the bottom up that spans recent instances of protest in Turkey, but, each in their own way and for their own distinct field, they find a new approach to individual and collective archives to present the themes of looking and surveillance and counter-surveillance from an eye-opening perspective. As we feel more and more surrounded by prying eyes, it is our duty to keep our eyes or our camera-eyes on those watching us and to remind ourselves of the direction of our relationship with those we look at with the cameras in our own hands.

To resolve all ethical problems that are involved when we are holding a camera, Oktay İnce says in his video, we must go to the very bottom. This conclusion is reminiscent of the way Rimbaud expressed his desire to get rid of his identity, to become someone else, to descend to the bottom, saying, “I am of inferior race for all eternity (…) I am a beast, a negro”*… When we realize that the representation of otherness is impossible and that we have to get as close as possible to this impossibility, then perhaps becoming this other is another way of seeing from below… Like Oktay İnce lying all the way down and entering a dialogue with a dog, watching city life through walking feet from there, from below… The From Below series reminds us once again that the camera, for years taken to look down vertically from top to bottom, can also do the opposite and how essential this is for us to set our focuses of resistance.

* Quoted in Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2, The Time-Image, University of Minnesota Press, 1997, p.153