Many filmmakers active in the independent cinema of Turkey today met in the courses organized by Mesopotamia Cultural Center (MKM, Navendên Çanda Mezopotamya) in the 1990s and developed a collective working practice under its cinema branch. Now, MKM has been asked by the local municipality to evacuate its building in Tarlabaşı, Beyoğlu, where it has carried out its activities since 1991.1

Özcan Alper, the director of influential films such as Sonbahar (Autumn, 2007) and Gelecek Uzun Sürer (Future Lasts Forever, 2011) was one of the filmmakers who were active in MKM’s cinema branch. He wrote about the impacts of the MKM tradition on the cinema culture and practices in Turkey.

By Özcan Alper

I first came into contact with MKM back in 1995, when I had finally made the decision to study film for a second university degree. After visiting several film schools and attending some classes as a guest student, I quickly changed my mind and decided not to study film. I had the impression that, just as education in a Physics department kills our curiosity for science, schools offering film education would have a similar impact, which made me altogether give up the idea of attending a university to study film. Instead, in order to get some basic cinema knowledge, I began to search for independent film courses that were becoming popular in Istanbul back then, although still few in number. Upon the suggestion of a friend, I went to Mesopotomia Cultural Center (MKM), where I first met Özkan Küçük2 and then decided to enroll in the cinema course planned to start the next semester and last for a year. My time there extended over a period of about four years in total.

The perspective and politics put forth by this cultural center have played a crucial role even in the survival of Laz, Hamshen, Georgian, Pontic Greek and Circassian languages in the Black Sea region.

While I was attending the course, the first building in Tarlabaşı3 was also active, but theater, music and cinema branches carried out most of their activities in the venue on İstiklal Street, where we received cinema training courses right behind the café section, in an area of about 10 square meters, without any windows. Before moving on to the cinema training there, I’d like to point out the most remarkable aspect of that era of MKM: As unofficial bans on especially the Kurdish language persisted in different ways, people there were engaged in serious artistic production in music, theatre and other branches despite very hard conditions. For instance, music bands in diverse genres made their best productions during that period. The journal ‘Rewşen’, published by MKM, was another good example of artistic productivity. All these were important not only to the Kurdish language and enlightenment but also to all the languages and cultures threatened by the state in Turkey at that period. MKM provided a new focus and hope for them as an idea and as a means of struggle to re-establish themselves against all kinds of denial. Indeed, it would not be an exaggeration to say that the perspective and politics put forth by this cultural center have played a crucial role even in the survival of Laz, Hamshen, Georgian, Pontic Greek and Circassian languages in the Black Sea region in spite of everything today.

As for the cinema course in MKM, first I should mention two people for their great contribution to us in terms of both theory and practice: Hüseyin Kuzu and Ahmet Soner, the chief instructors during our time there. In addition, many others from the sector such as Tül Akbal, Alin Taşcıyan, Semir Aslanyürek, Natali Yeres, Uğur İçbak, Hilmi Etikan, Enis Rıza, Zeki Demirkubuz and Yeşim Ustaoğlu (and many more whose names do not occur to me now) have also expressed their solidarity and shared their experience at MKM sometimes by offering only one lesson and sometimes teaching there for a month.

It was actually a time when we not only got to know classical cinema but also intensely engaged in discussions on the question of “What kind of a cinema?”.

I’d also like to mention some names who attended courses in MKM at the same period with me: Hüseyin Karabey, with whom I have collaborated with in some projects later on. Özkan Küçük and Kazım Öz, also Zülfiye Dolu, who later quit cinema, and Sami Mermer, who later went on with cinema as an immigrant in the USA and Canada, and many others. We worked like a cinema group during a period that lasted for a few years, until the beginning of 2000s. It was actually a time when we not only got to know classical cinema but also intensely engaged in discussions on the question of “What kind of a cinema?”. We would mostly examine the independent and political cinema movements and seek answers to the question of “What kind of productions can we make?” owing to both the political stance of our cultural center and the global political conditions in those years.

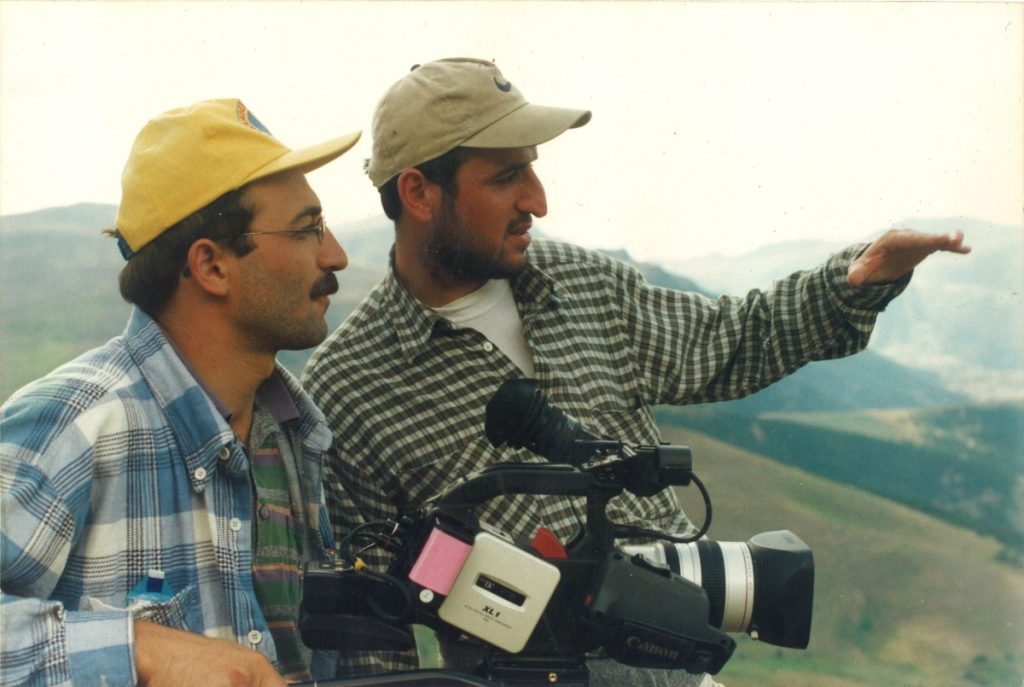

However, unlike today, digital cameras and digital technology were not widespread at that time, which offered both advantages and disadvantages. Kazım’s (Öz) short film Ax (The Land, 1999), co-written by the whole group at MKM, with an impact almost capable of changing the perspective on short films in Turkey, and his medium-length Fotograf (The Photograph, 2001) were outstanding and good movies of that era. I can also state that Hüseyin’s (Karabey) Boran (1999), a film on Saturday Mothers4, and Aydın Bulut’s documentary Gazi Mahallesi5 (1995) were significant for us in our quest to answer the question “What kind of a cinema?” back then. Another prominent documentary of this period was Ahmet Soner’s film on İsmail Beşikçi6 called İsmail Beşikçi: 36 Kitap = 13 Cezaevi (İsmail Beşikçi: 36 Books = 13 Prisons, 1997).

All these were pivotal in that they reflected a specific way of production. At that time, so many movies at differing lengths were produced and documents were recorded; we do not have a comprehensive inventory for that period, though. Back then, we occasionally came into contact with Miraz Bezar7, who was studying cinema in Hamburg. Istanbul Film Festival also brought us into contact, albeit shortly, with international filmmakers. I guess at that time the film that excited us most was Bahman Ghobadi’s Zamani barayé masti asbha (A Time for Drunken Horses, 2000), marking a turning point in cinema after Yılmaz Güney, especially for Kurdish filmmakers.

Another major advantage of this period was that in the preparation and shooting stages of her film Güneşe Yolculuk (Journey to the Sun, 1999), Yeşim Ustaoğlu worked with actors/actresses from MKM (in a way in relation to the content of the film), and we were also partly involved in the process. This was a big step for us as we had little chance to contact the “sector” due to reasons that had to do with us and the films produced back then. I can express that Journey to the Sun motivated and excited us all, both with its production phase and its screening in spite of all the pressures. Of course, another nice thing about MKM was that, as I myself have witnessed, it acted as a hub for immigrant and exiled Kurdish artists from Iraq, Iran and Syria as well as artists from Turkey. During that period, MKM helped raise many actors/actresses capable of acting in Kurdish in front of the camera. For instance, Nazmı Kırık and Feyyaz Duman acted in a lot of movies shot in Kurdish. Moreover, many actors/actresses from the theatre branch of MKM began to appear in roles of varying significance at films shot in Turkey such as those of Handan İpekçi and Sedat Yılmaz (though he shot Press much later, in 2010.) Right after this period, apart from fiction filmmakers, many documentary filmmakers like Çayan Demirel, Güliz Sağlam and Veysi Altay were also in contact with MKM in some way.

MKM was also influential in that it set an example for many leftist political movements dissolved with the military coup of September 12, 1980 in their struggle for revival, especially in the cultural sphere. We can claim that, to a large extent due to the impact of the cinema branch of MKM in the second half of the 1990s and the beginning of 2000s, the left began to question its closeness to written (rather than visual) production, and its insistence on being active in only publishing books and magazines. This led to the opening of film courses in a lot of leftist cultural centers during those years, which has obviously influenced a new generation wishing to make films (independent, political or whatever we want to call them) beyond the dominant discourse in Turkey, even in the absence of spatial interaction.

For all peoples (not only Kurds) who have been silenced and threatened with destruction in this country, MKM represents a will of singing, writing and filmmaking in their native languages.

Today, it is crystal clear that the unjust and unlawful effort to evict MKM from its building in Tarlabaşı is a political move as for all peoples (not only Kurds) who have been silenced and threatened with destruction in this country, MKM represents a will of uncompromising resistance against such repressiveness through singing, writing and filmmaking in their native languages. This is a truth much beyond rhetoric.

Translation by Duygu Çınga

NOTES

1 “Mesopotamia Cultural Center (MKM) to be evicted from its building in İstanbul”, Susma24, 19 August 2020.

2 Editor’s note: Besides his short fiction Pepûk (2013), Küçük made various documentaries, such as Yıllar Sonra, İşte Diyar-ı. Bekir (Years later, Here is Diyerbekir, 2003) and Li Serxaniyên Diyarbekiré (On the Rooftops of Diyarbakır, 2005). He also contributed to Altyazı Fasikül’s Looking Outside film programme with a short video-essay on Diyarbakir called Li Kûçeyên Diyarbekirê… (Walking the Streets of Diyarbakır, 2020).

3 Editor’s note: The building which MKM has been asked to evacuate today.

4 Editor’s note: A group of people mainly composed of mothers staging weekly sit-in protests for their enforced disappeared relatives and demanding justice for political murders in Turkey. On Saturday, September 26 2020, they held their 809th protest in Galatasaray Square. Reminiscent of Argentinian ‘Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo’.

5 Editor’s note: A documentary about the 1995 Gazi Quarter riots which began after drive-by shootings on several cafés at the Gazi Quarter in Istanbul, where mostly Alevis live.

6 Editor’s note: A Turkish sociologist who dedicated his life to Kurdish Studies. Prosecuted many times for his books and articles, in total he served 17 years and 2 months prison time. İsmail Beşikci Foundation was established in 2011 to perpetuate the struggle of İsmail Beşikci.

7 Editor’s note: Miraz directed his debut feature Min Dît (Ben Gördüm) in 2009.