Cinephiles around the globe have been deeply concerned about and reacting against the closing of the Brazilian Cinematheque by Jair Bolsonaro’s government. After months of protests, forums and campaigns such as ‘S.O.S. Cinemateca Brasileira’ what is the situation today? Will the institution re-open and the audiovisual memory of the country be preserved? Film scholar at Indiana University Darlene J. Sadlier, who is writing a book on the history of Brazilian documentary cinema, reports on the current situation.

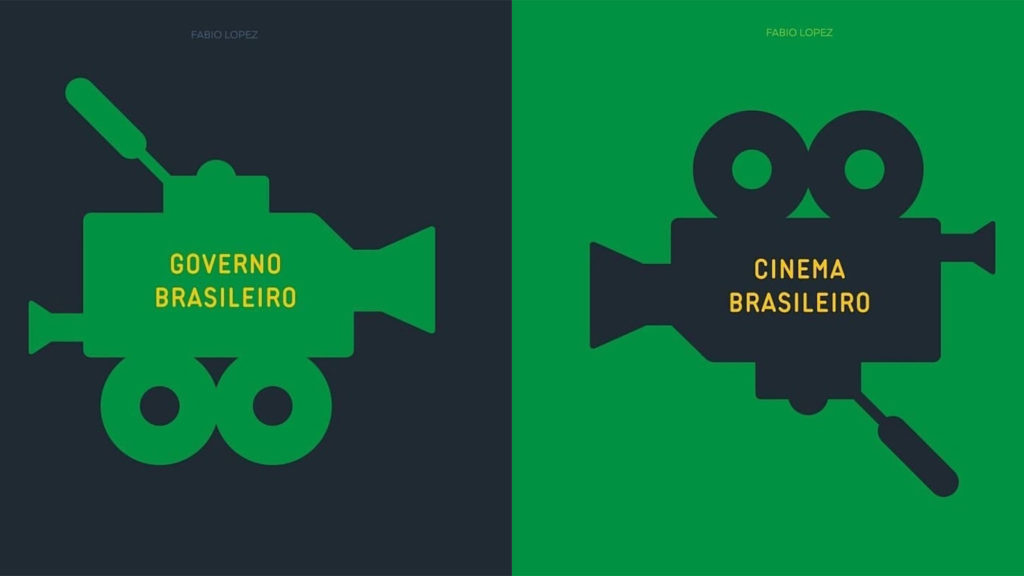

The arts and culture in general are suffering everywhere from the global pandemic, but in Brazil the situation is especially dire. Soon after taking office in January 2019, President Jair Bolsonaro dismantled the Ministry of Culture, and in December that year, his government failed to renew its contract with the Association for Educational Communication Roquette Pinto (ACERP) for the operations and management of the Cinemateca Brasileira (CB). The government’s displeasure with the perceived left-liberal content of certain programs televised on ACERP’s education channel influenced the decision not to renew. ACERP immediately requested an emergency contract to maintain the CB’s forty-one-member staff to ensure the safety of flammable nitrate reels stored in temperature-controlled rooms, as well as other audiovisual requiring frequent inspection. Despite the loss of its contract and funding, ACERP continued to pay utility bills, but staffing was reduced. As the months passed, those who stayed on worked as unpaid volunteers to protect the nation’s audiovisual memory.

On August 7, 2020, the government sent armed federal police to accompany Hélio Ferraz de Oliveira, acting head of the Secretariat for Audiovisual and collect the keys from ACERP, closing the Cinemateca Brasileira. The remaining staff was dismissed and services and utilities were discontinued. A public hue and cry rose over the real possibility of fire and major losses to the country’s patrimony unless electricity and other utilities were resumed. The September 2018 fire that destroyed the National Museum in Rio de Janeiro was all too fresh in the public mind. Acquiescing, the government restarted utilities and hired a small non-specialist crew for basic security purposes. Despite government assurances at the handover of keys that a call for a new management was forthcoming, no action was taken. All the while online research guides to the CB’s vast collections continued to be accessible, until a city power outage in early November. Lacking trained staff to reconnect them, three main catalogs with documentation, images and collections of digitized films from the CB’s research website “Bank of Cultural Contents” remain offline.

In late December 2020, a news release announced that the Sociedade Amigos da Cinemateca (Friends of the Cinema Society, SAC), a longstanding patron and social organization, was about to receive a temporary three-month contract to rehire staff and resume partial operations by mid-January 2021. After months of online forums and debates, “S.O.S. Cinemateca Brasileira” protests and publication of proclamations, manifestoes and articles locally and internationally in support of the institution, word of the re-opening under SAC management raised hopes for the new year. That hope still exists, but to date no contract has been signed.

The Cinemateca Brasileira is South America’s largest audiovisual center, housing more than 250,000 reels of film representing some 30,000 domestic and international titles and an estimated one million documents. Archives of major directors such as Glauber Rocha, Carlos Diegues, Carlos Reichenbach and Ana Carolina, of film companies like Atlântida and Vera Cruz, of the state agency Embrafilme, and of CB founder Paulo Emílio Salles Gomes are among the many housed there. Its conservation efforts and preservation facilities are world-renowned, with digital capacities alone enabling the transfer of 8mm, 9.5mm 16mm and 35mm to HD, 2K, 4K and 6K. Digitized materials include 6,322 films, 3834 Brazilian and international film posters, 53,381 production stills and 24,354 other items ranging from TV Tupi news scripts (1950-1980) to all issues of the prestigious journal Filme Cultura, first published in 1966.

Occupying an area of over 250,000 square feet, the CB headquarters has two movie theaters; a café; a research library; four climate-controlled rooms, two for color and two for black and white films; four rooms in a separate area for nitrate films, each with a capacity of 1000 reels; plus office and exhibition spaces. Separate areas contain films with deterioration, copies of films for exhibition, and the vast video and digital collections. There are also laboratories with equipment for conservation and preservation. A large outdoor screening facility with a 43 x 18 feet screen offers 35mm and digital projection. All this and more has been locked up by a splenetic government, with still no word on its temporarily funded release.

Like cinemas around the world, the CB exhibition spaces were closed to the public in March 2020 because of the pandemic. But documentation and preservation work continued while students and scholars writing theses, dissertations, articles, and books still had access to materials. It is impossible to estimate the damage to specialist careers and to academic research and scholarship as a result of the CB’s forced closing. The closing also impacts filmmakers and others whose film and paper collections are housed there, and to which they need and deserve access.

It should be recalled that the CB was host of the 2006 Visible Evidence Conference, where, among the many memorable film showings, members witnessed a special exhibition of Glauber Rocha’s Di Cavalcanti (1977), a documentary that offended the Cavalcanti family with its grotesque images of the artist in his coffin, and which had been held from public view for decades. The CB sought and received permission from the Cavalcanti family to screen the film for this specialized audience.

As a Brazilianist and film scholar, I have conducted research for several books in the CB, including volumes on Nelson Pereira dos Santos, U.S.-Latin American cultural diplomacy during World War II, and my current project on Brazilian documentary film. In 2016, while teaching a graduate seminar at the Universidade de São Paulo about U.S. government films produced by Nelson Rockefeller’s Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs, I was given a special tour of the CB’s large headquarters. There I saw up close the impressive preservation set-up and saw the CB’s beautifully restored version of Rex Lustig and Adalberto Kemeny’s São Paulo: Sinfonia da Metropole (1929), a little studied symphony film, which was soon to be screened at the Pordenone Film Festival. This film and the early research I conducted at the CB at that time became part of the chapter on silent cinema in my documentary project. Fortunately, I was able to return several times to the CB to continue research as well as to screen from home in the U.S. their digitized collection of archival films, including dozens of educational shorts by the National Institute for Educational Film made during and after the Getúlio Vargas’ New State dictatorship (1937-1945).

All those resources and much more are now unavailable to individuals who, whether for research or general interests, wish to access them. One can only hope that the government carries through with its promise and signs a contract to return to the people of Brazil the audiovisual memory of their nation’s history, which is rightfully theirs, and which the film world needs.