Seen Unseen: An Anthology of (Auto)Censorship is a collective rumination on various forms of censorship, echoing Jean-Pierre Gorin’s notion of the ‘essay film’—a form that “multiplies the entries and exits into the material it has chosen (or by which it has been chosen).”

In 2007, French filmmaker and theorist Jean-Pierre Gorin curated a seminal film program for Vienalle entitled ‘The Way of the Termite: The Essay in Cinema.’ In the introduction text, he defines ‘the essay’ in film as follows: “The essay is rumination in Nietzsche’s sense of the word, the meandering of an intelligence that tries to multiply the entries and the exits into the material it has elected (or has been elected by). It is surplus, drifts, ruptures, ellipses, and double-backs. It is, in a word, thought, but because it is a film it is thought that turns to emotion and back to thought.” Although not an essay film by definition, I believe, this description of “multiplying the entries and the exits into the material it has elected (or has been elected by)” perfectly encapsulates the essence of Seen Unseen: An Anthology of (Auto)Censorship, a collective rumination on various forms of censorship.

The idea for this video series emerged during an evaluation meeting for the previous video series From Below, also produced by Altyazı Fasikül. However, the theme has been present since the outlet’s inception. Altyazı Fasikül is a spin-off project of Altyazı Cinema Magazine, a well-known address for criticism in Turkey. Founded in 2019, Altyazı Fasikül came into being at a time when the boundaries between censorship and self-censorship in Turkey were becoming increasingly blurred. As an outlet focused on the freedom of artistic expression in film in Turkey, one of Fasikül project’s primary goals was to resurface stories of censorship, at a time when silence on the cases was becoming eerily pervasive. Censorship was being normalized, becoming all too widely accepted, and the silences surrounding it seemed to be prevailing. In short, not only the Fasikül itself but this anthology film project as well surely had been selected by the material itself.

The initial idea for making a video series by Altyazı Fasikül arose during the early months of the pandemic, a period marked by a different kind of enforced silence in public spaces. It was easy to anticipate that many interesting stories would emerge from these experiences; yet, the aim of this series was not merely to document the novel experiences of the pandemic, but rather to create a solidarity network among video activists, photojournalists, and documentary filmmakers, whose work was inherently social and who, like the rest of us, were fighting against isolation and confinement. The goal of Looking Outside was to remember the collective struggles on the streets when ‘locked inside’, during a time when we could also reflect together, utilizing our archives, dreams, and fears. The process of developing this improvised and adaptive collective approach was empowering for everyone involved. It was a communal practice intertwined with individual artistic expression, which inevitably led to the creation of a second series. ‘From Below’, focused on examining images during a time of intense surveillance in Turkey, when even documenting social struggles was easily criminalized. Our ‘mission’ was to empower the gaze from below, representing workers’ voices, women’s voices, going through archives that were not there, staring back at those watching us, and even trying to see the world through the eyes of a stray dog.

Blurred Boundaries

The third series of Fasikül, ‘Seen Unseen’, became an anthology consisting of six short videos that reflect on self-censorship from various angles which all engage in a dialogue with each other. Fırat Yücel, who is also the artistic director of Seen Unseen, opens the series with his prologue, Doubts, a reflective process about trying to make a documentary about the Gezi Resistance, a spontaneous people’s uprising initially to save a park in Istanbul, but quickly transforming into a mass protest against the ruling AK Party government. This prologue not only introduces the project to the audience but subtly alludes to all other films in it. It marks Gezi, as it is known in Turkey, as a pivotal moment in the history of the country that resulted in a suffocating crackdown on free expression.

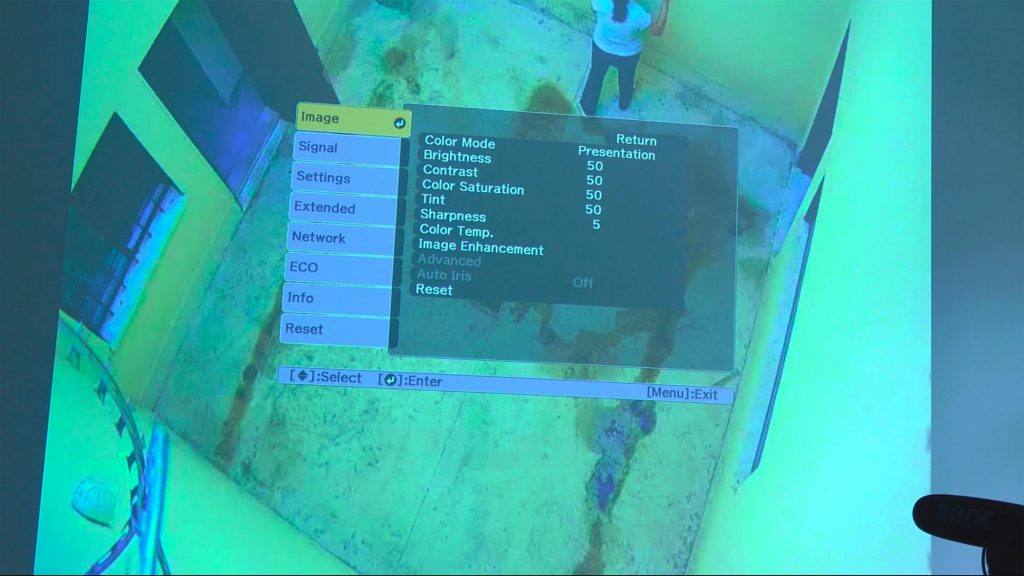

Even before Yücel’s introductory video begins, there is a prior image in the project, that appears at first almost as an apparition. It is a recurrent image that is so unbelievable, that one thinks it must be faked. The piece is called Walls, and it is composed entirely of a single shot taken by a surveillance camera inside what appears to be a prison courtyard, with barbed wire cutting through the lower left corner of the frame. In it we see the blurry figure of a prisoner approaching the far wall, writing something in large letters. Is it a slogan? a message? We don’t yet know.

The anthology begins with this image projected onto another wall, outside the prison cells, where the video-makers discuss adjusting, reframing, and refocusing the image, adding a new voice-over, or a commentary. This onscreen action itself encapsulates what this anthology is all about: thinking with images, through images; reframing, refocusing, and recontextualizing them.

A contextual note arrives, mentioning that after the suppression of the Gezi Resistance in 2013, censorship cases became severe, leading to an inevitable increase in self-censorship. This anthology contains six videos “where the boundary between auto and authority was blurred within a climate of censorship.” As such, the anthology blurs the boundaries between experiences of censorship and self-censorship.

When in Doubt

In the Prologue: Doubts, two anonymous characters (an owl and a cat) text each other about making a film on the Gezi Resistance. The discussion revolves around the ethics and politics of its representation: whether it is possible to represent such a multifaceted, multi-affective revolutionary movement where everything everywhere is happening all at once, and indeed, what the makers want to say about Gezi after all these years. By the end, they ask each other, how is it possible to know if their decisions about what to include are crafted by their political stance or their fears? Doubts accompany us through these winding neural pathways formed in our brains in a climate of censorship, where the boundaries between auto and authority are blurred. The etymological connection between ‘the origin within oneself’ (auto) and the origin/source of power (authority) hints at the intertwined nature of censorship, whether it is enforced from outside by the authorities or self-imposed.

For many participants and witnesses, the Gezi uprising felt like the funeral of the mainstream media. Everyone had to become a citizen journalist or a video activist, as the lies of the mainstream news media were too obvious. Millions of individuals had to become the bearers of their own news, sharing their own stories and truths from firsthand experiences through social media.

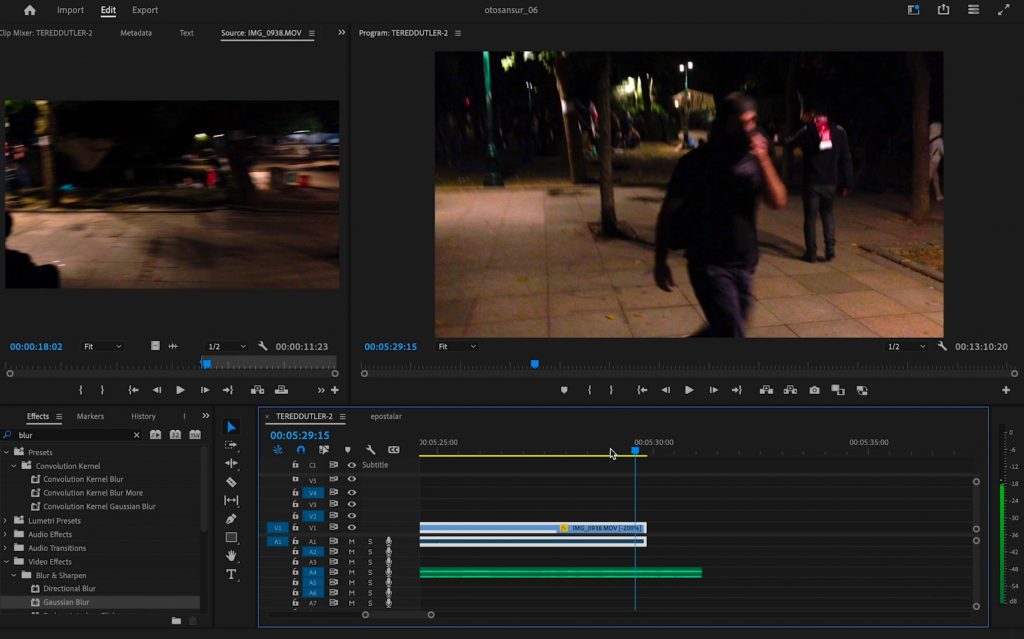

Yet, after more than ten years, with the censorship cases, trials, and punishments revolving around Gezi documentaries and more, the stories that surfaced into full view during Gezi have been pushed back out of sight. Hence, Doubts is certainly more a film about the fears of representing Gezi today rather than it is a film simply about “those days”. It is a film of hesitation, the fear that unexpectedly arises from a knock on the door. But it is also a film about all the other emotions that tend to be overshadowed by this fear: the courage, the joy, the solidarity. It is also a film primarily about form. It dissects the tools of aesthetic oppression on an operating table: the editing software. The eerie music, the blurry image, the slow motion, the wide shot… It examines how these aesthetic choices and formal tools can serve fear itself. It opens the discussion on the politics of image for all other films in the anthology.

At one point in the video, a series of names flash across the screen: documentary filmmakers and video activists who have faced trials or been sentenced simply for filming, editing, or even contemplating a documentary about Gezi. It is a rapid record of what documentary film has endured over the past ten years. This sequence also serves as a bridge to another video in the anthology, Missing Documentaries by Sibil Çekmen.

Frames from unfinished/unreleased films referenced in Missing Documentaries

Presence and Vulnerability

Missing Documentaries derives from Çekmen’s comprehensive academic research project on the recent history of documentary film in Turkey. She interviews many filmmakers, asking them about the documentaries they were unable to start, continue, finish, or screen, and the various reasons behind these false starts. We are once again on a computer desktop, this time going through Çekmen’s folders. The video starts with an overflow of images from different times and places, “images that call each other, that converge and collide, which are suspended together in my mind and my desktop,” her voiceover explains. Images of violence, bombings, protests, memorials, red carnations… Throughout the video, filmmakers including Nejla Demirci, Aynur Özbakır, Bingöl Elmas, and İlham Bakır narrate their personal histories of being unable to complete their films and the reasons why.

Aynur Özbakır shares candidly the affective difference between being present with her camera during a traumatic event and later, when she is left alone with the material, reviewing, and editing. She describes how the material weighs heavily on her and speaks about her struggle to find the energy or will to continue making her film. However, her account doesn’t end there. After the video interview, she couldn’t resist sending another message, explaining that she felt she sounded too pessimistic and was uncomfortable with it. This moment of her expressing concern and responsibility about the impact she might have on others is very valuable. The transparency and complexity of emotions articulated responsibly and openly with a self-critical distance, highlight an effective way to deal with self-censorship. Representing themselves as vulnerable individuals subjected to various forms of violence, and also as agents taking action in the face of censorship, underscores the dual nature of self-censorship.

Maybe Missing Documentaries ends sooner than it should, acknowledging its fate as a half-finished work, noting that censorship cases continued to occur even as Sibil Çekmen was editing the video.

Personal Herstories

Serra Akcan’s Dear F is a letter written by the narrator, addressed to someone she met during a visit to her family village after her father’s passing. In search of her family lineage, she attempts to uncover a past that was always half-told, a missing story. At first glance, Dear F‘s ties with censorship might seem weaker than the other films. However, the broader context surrounding these untold stories revolves around one of the most heavily censored subjects in the history of Turkey: the Armenian Genocide, suppressed through judicial penalties and state policies denying its recognition.

The images accompanying letters in Dear F are mostly black-and-white stills. These still images often carry a subtle potential for movement; at times, like the flicker of a bird, barely noticeable motion appears, giving a fleeting sense of something more beneath the image. Occasionally, in some scenes, the stills transform into their negatives. Sometimes, on the soundtrack, the film chooses silence, at other times, words echo without visual accompaniment, as this piece also reckons with the impossibility of representation of collective traumas. Through the filmmaker’s encounters, we realize that her family denies their Armenian lineage (as a consequence of conforming to official ideology or the pressures it imposes, consciously or unconsciously), leading to moments where conversation becomes impossible. Sometimes a window for dialogue opens but soon fades away abruptly, and sometimes even violence erupts.

Akcan also recounts her visit to Armenia, this time using a contact sheet as she searches for a particular moment, a photograph. She vividly recalls a child’s expression upon learning she is from Turkey—a look of fear in his eyes, as if he has seen a monster. The absence of the image itself, when she admits she will never forget that look, intensifies the emotion. The image need not be there; the memory of the look is powerful enough. In other cases, the people she meets in Armenia ask her about their hometowns—Van, Adıyaman, Malatya. They wonder if these places are still as green as they remember. The absence of images for these individuals also speaks volumes, conveying the longing and emotional resonance of their questions.

But the most powerful image is when two women musicians from Turkey, one Armenian, and the other Kurdish, Dengbej Gazin and Aşık Leyli, start singing and dancing together under a strong breeze in front of a vast landscape. At that exact moment, the images come alive. The narrator, who is grappling with this violently repressed, silenced history, allows these two powerful women storytellers, to rupture the silence, hand-in-hand.

Mocking Criminalization

Nadir Sönmez’s Cruising explores a space–this time surrounded by invisible walls, a park encircled by the masculine audiotrack of the autobahn. The sarcastic tone of this video stands out within the anthology. It presents an imaginary petition to the UNESCO World Heritage Center, arguing that certain cruising areas should be added to the World Heritage list to protect the natural habitat for gay men in Istanbul.

The use of music in Cruising reminds us of the discussion in Doubts, where the two characters talk about how eerie music functions as a tool of criminalization. In Cruising, this eerie tone has an ironic twist. The bleeping (self-censoring) of the location’s name, the black-and-white slow-motion aesthetics, and the camera cruising around the space at night in absolute anonymity all serve to mock and decipher the formal aesthetics of criminalization. However, this ‘self-reflexive censorship’ is double-edged. It also functions to protect these spaces from the oppressive gaze, for the safety and anonymity of these areas. Therefore, we are introduced to a discussion of another form of self-censorship, aimed at avoiding potential harm.

Losing Focus

The final film in the anthology is belit sağ’s Sevil, a singular account of the censorship experienced by the artist Sevil Tunaboylu during an exhibition. The video serves as a sincere record of genuine emotions during a process of violent censorship, as well as the varied emotions that follow such trauma, approached with a self-reflexive critical perspective. What is particularly valuable in sağ’s film is the vulnerability portrayed—the experience of being forced into the role of a solitary subject—and how the meaning transforms when these experiences are spoken and shared, given language and a place in the world as a narrative.

Despite being a simple conversation shot via Zoom, belit sağ poetically manipulates the image, capturing hesitations and the blurred lines between censorship and self-censorship. Through visual techniques, the film reveals Selvi Tunaboylu’s experience as a process of fragmentation and confusion. The story revolves around her struggle with presenting an artwork she created, which was attacked physically during an exhibition. Under a new climate of fear, she hesitates to submit the painting for an article discussing the incident later on.

As she discusses the overwhelming emotions she goes through, the image and sound become eerie, losing focus. She reflects on her decision not to include the painting in the book—initially feeling relief, followed by shame, then relief again, trapped in a cyclical pattern. This inertia is palpable as sağ blurs the image and makes it harder to focus on, while the layered echoes of voices intensify the scene.

At the same time, sağ incorporates images from Tunaboylu’s 16-piece installation, scattering them across the screen to reconstruct the whole piece on screen, neither singling out nor erasing the particular image that was censored before. It depicts a process of recovery.

Climbing up the Walls

Lastly, returning to the Walls, we revisit the image of the prison cameras. The notion of the “image as evidence” grows stronger as we continue to observe it. The date at the top of the screen, the time code that can be followed, and some numbers possibly identifying the camera’s position amplify the uneasiness. It dawns on us that our gaze aligns with the oppressor’s gaze. Can we change our angle?

The voiceover liberates us from the guardian’s viewpoint; the prisoner begins to speak. She reflects on the power of books in prison: “It depicts a place; you envision that place in your mind. A book nourishes your mind and imagination. It prevents you from disappearing. In such confined spaces, books make the walls dissolve. It feels as if you’re on top of the wall. That’s why they ban books in prison.” This act of suppression penetrates even the imagination, forcing an internal dialogue that shapes resistance and behavior under threat. It illustrates the intricate tension between censorship and self-censorship in the face of severe repression.

Faced with the banning of books and the harsh reality of resisting this punishment while already in prison—along with the risk of further reprisals for defending one’s rights—one is affected on many levels. This internal dialogue inevitably shapes behavior, even during moments of resistance. It exemplifies the complex interplay between censorship and self-censorship when confronted with severe acts of suppression.

The testimonies in this anthology collectively prompt us to reflect on the processes that shape our thoughts and actions. They underscore that the most insidious form of censorship is silence itself—the hidden processes obscured by institutions, individuals, festivals, biennials, programmers, curators, editors, and most of all, perhaps ourselves. These veiled mechanisms perpetuate grave injustices and hinder efforts to openly confront and address these (open) secrets. At the same time, the project considers the fine line between what we call censorship, even self-censorship, and discretion, when it may be unsafe or unwise to expose an act or a fact when bravery can just be foolhardiness. This thoughtful anthology admits that judgment is still valuable and necessary, even if imposed and internalized censorship should be broadly opposed.

Ultimately, this anthology strives to explore its subject from multiple perspectives and narratives in an interconnected manner, making a concerted effort to resist imposed silences. It’s an attempt to climb up on a wall in times of severe censorship and self-censorship, through ‘political video essays’ that are in the end “thoughts that turn to emotions and back to thoughts”.

My heartfelt thanks to Alisa Lebow and Aslı Özgen for taking time to read and share their insightful comments with me.